Inference-Time Compute Scaling Methods to Improve Reasoning Models

Part 1: Inference-Time Compute Scaling Methods

Improving the reasoning abilities of large language models (LLMs) has become one of the hottest topics in 2025, and for good reason. Stronger reasoning skills allow LLMs to tackle more complex problems, making them more capable across a wide range of tasks users care about.

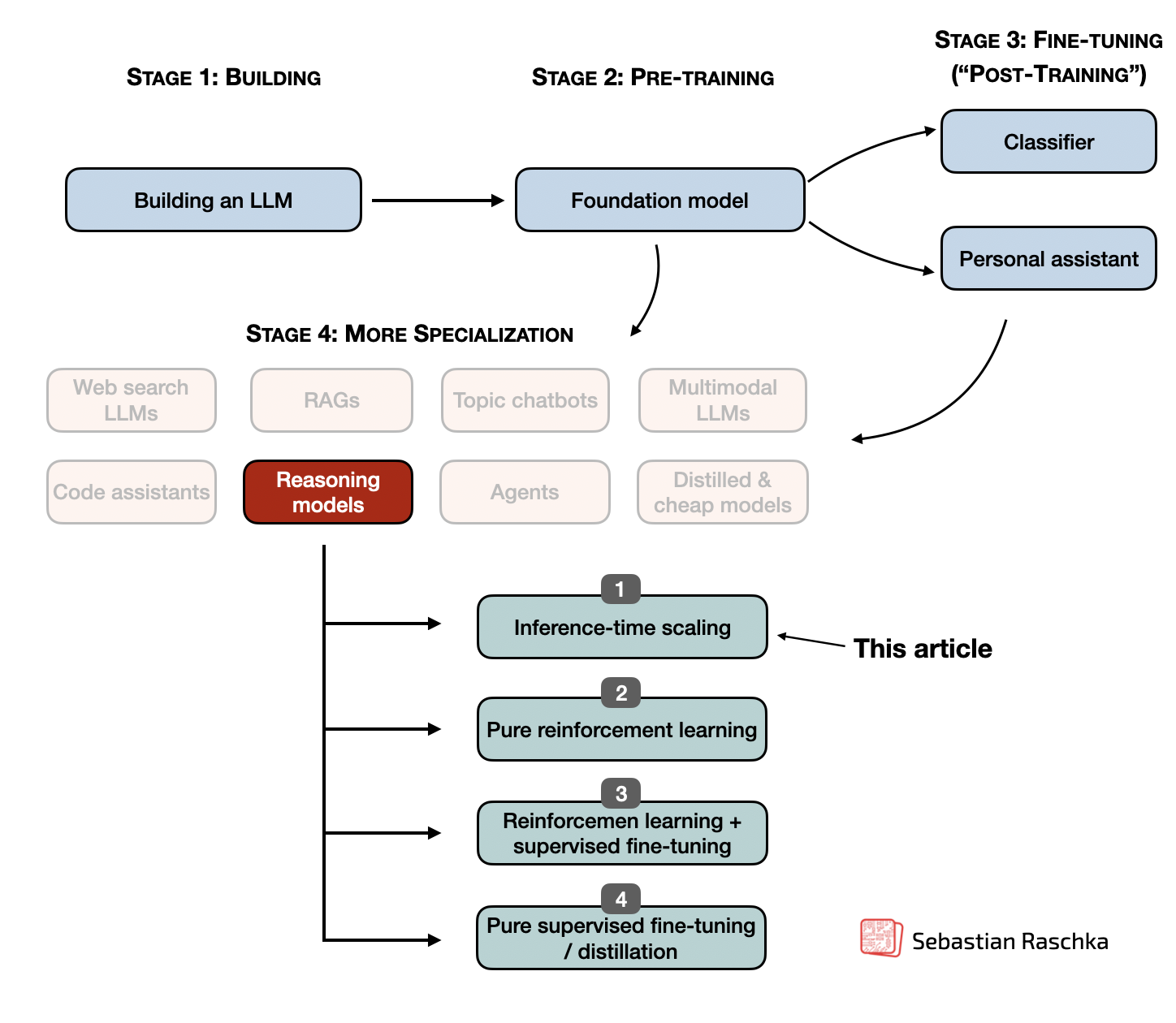

In the last few weeks, researchers have shared a large number of new strategies to improve reasoning, including scaling inference-time compute, reinforcement learning, supervised fine-tuning, and distillation. And many approaches combine these techniques for greater effect.

This article explores recent research advancements in reasoning-optimized LLMs, with a particular focus on inference-time compute scaling that have emerged since the release of DeepSeek R1.

Table of Contents

- Implementing and improving reasoning in LLMs: The four main categories

- Inference-time compute scaling methods

- 1. “s1: Simple test-time scaling”

- Other noteworthy research papers on inference-time compute scaling

- 2. Test-Time Preference Optimization

- 3. Thoughts Are All Over the Place

- 4. Trading Inference-Time Compute for Adversarial Robustness

- 5. Chain-of-Associated-Thoughts

- 6. Step Back to Leap Forward

- 7. Scaling up Test-Time Compute with Latent Reasoning

- 8. Can a 1B LLM Surpass a 405B LLM?

- 9. Learning to Reason from Feedback at Test-Time?

- 10. Inference-Time Computations for LLM Reasoning and Planning

- 11. Inner Thinking Transformer

- 12. Test Time Scaling for Code Generation

- 13. Chain of Draft

- 14. Better Feedback and Edit Models

- Conclusion

Implementing and improving reasoning in LLMs: The four main categories

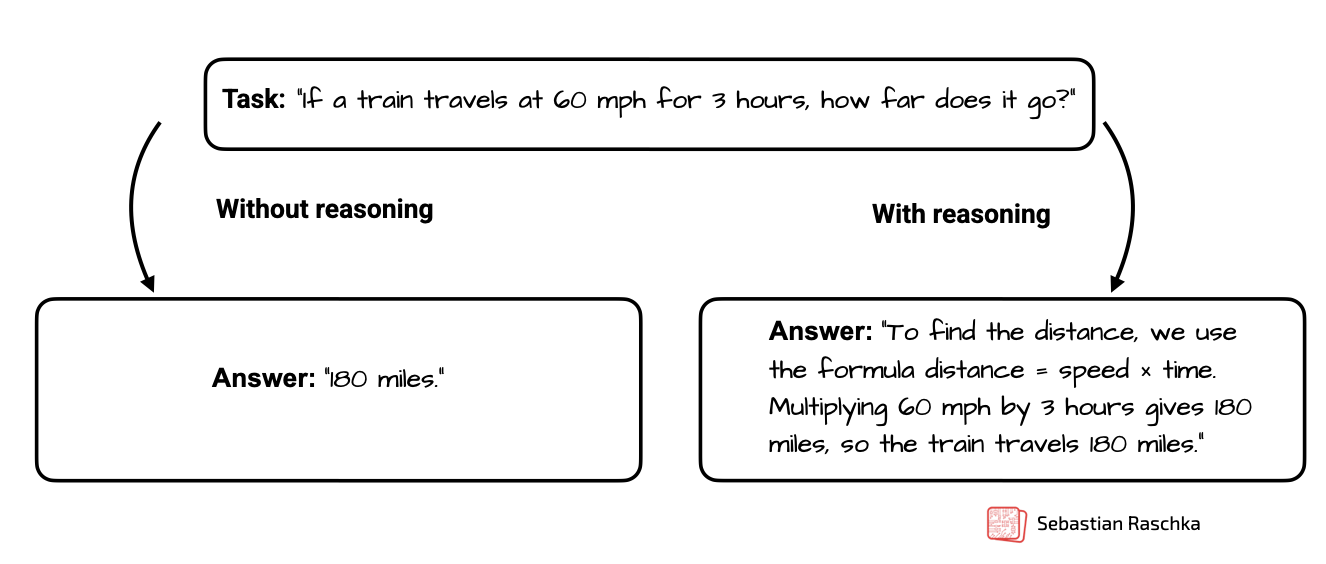

Since most readers are likely already familiar with LLM reasoning models, I will keep the definition short: An LLM-based reasoning model is an LLM designed to solve multi-step problems by generating intermediate steps or structured “thought” processes. Unlike simple question-answering LLMs that just share the final answer, reasoning models either explicitly display their thought process or handle it internally, which helps them to perform better at complex tasks such as puzzles, coding challenges, and mathematical problems.

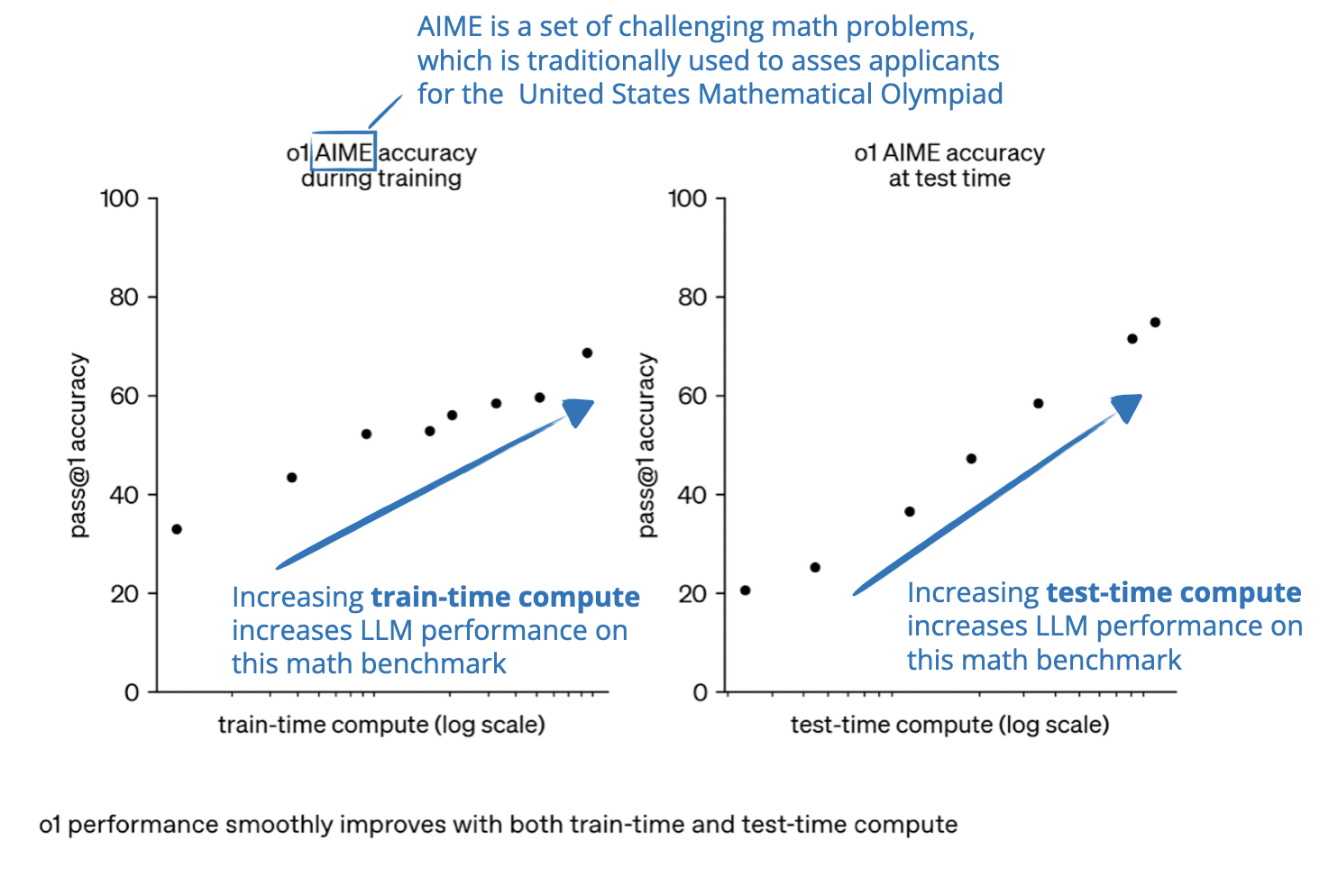

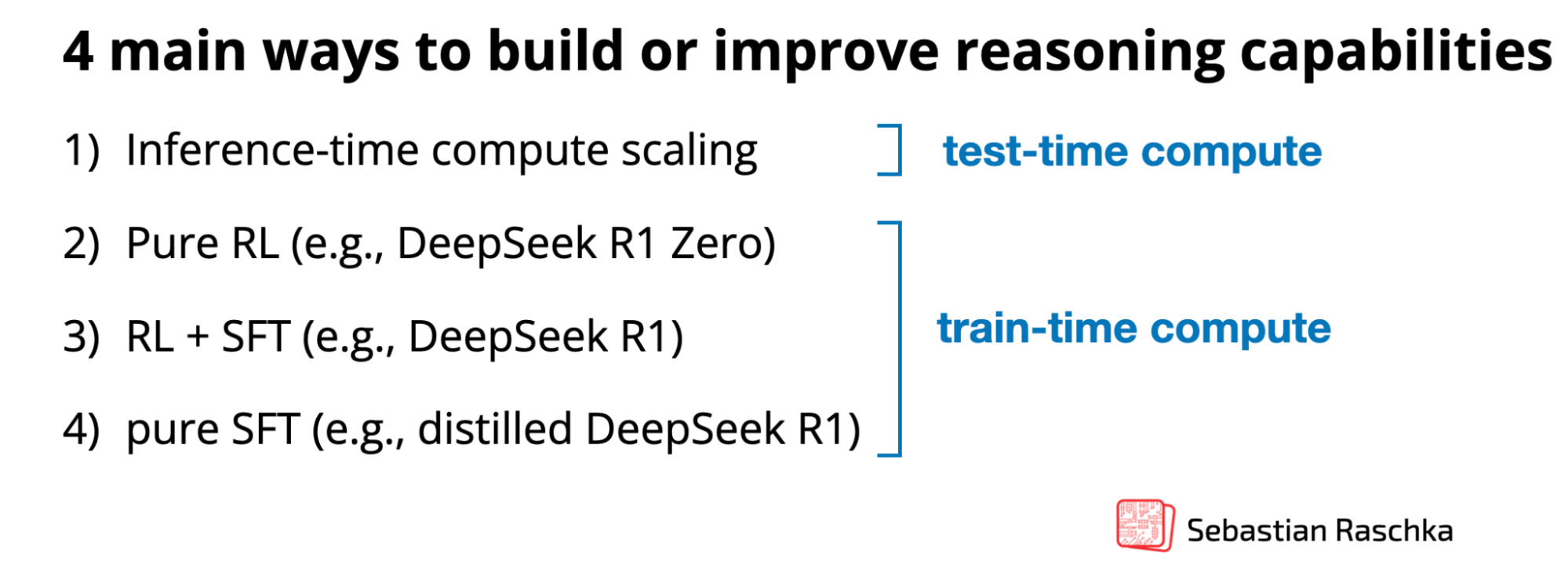

In general, there are two main strategies to improve reasoning: (1) increasing training compute or (2) increasing inference compute, also known as inference-time scaling or test-time scaling. (Inference compute refers to the processing power required to generate model outputs in response to a user query after training.)

Note that the plots shown above make it look like we improve reasoning either via train-time compute OR test-time compute. However, LLMs are usually designed to improve reasoning by combining heavy train-time compute (extensive training or fine-tuning, often with reinforcement learning or specialized data) and increased test-time compute (allowing the model to “think longer” or perform extra computation during inference).

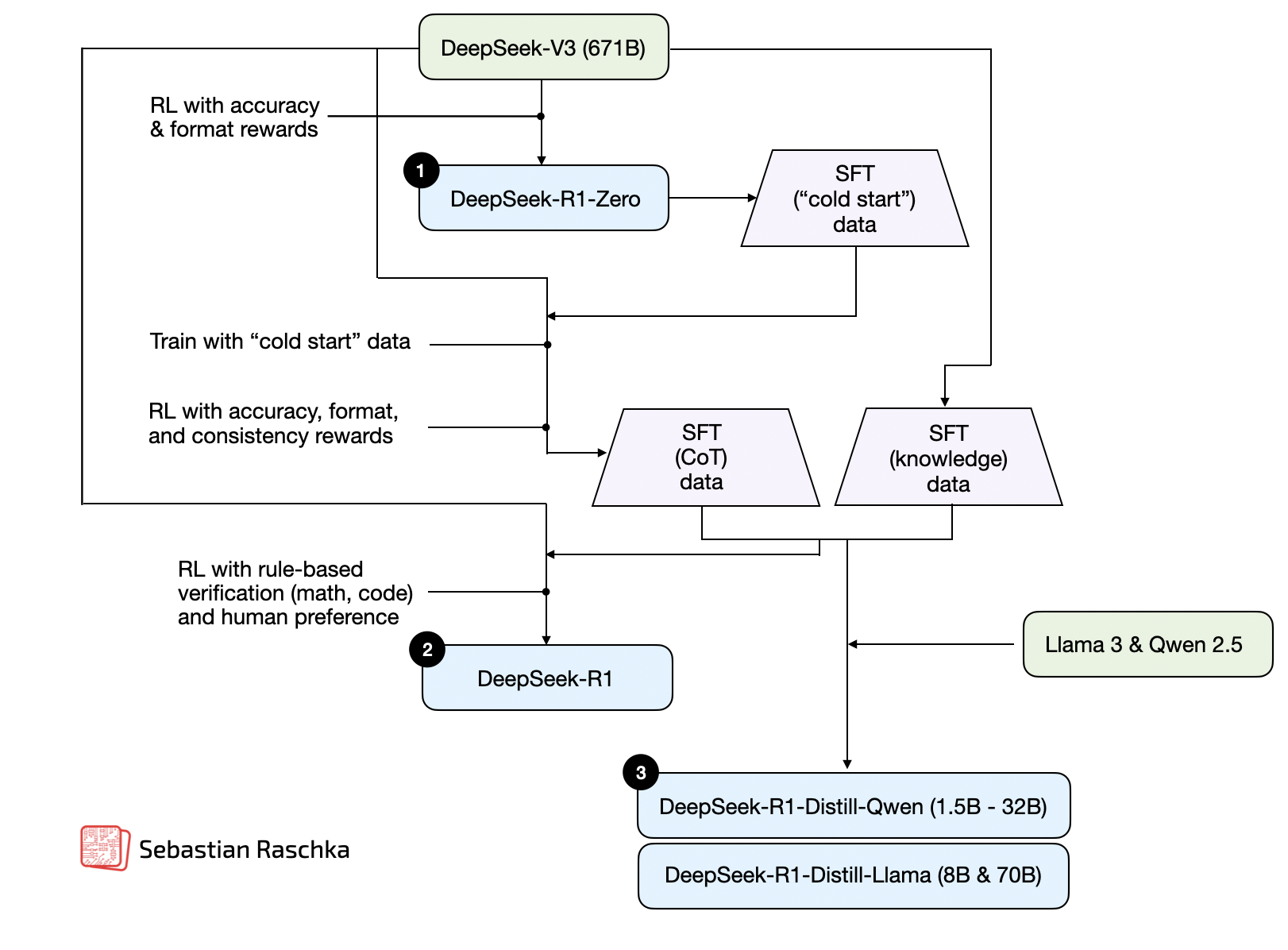

To understand how reasoning models are being developed and improved, I think it remains useful to look at the different techniques separately. In my previous article, Understanding Reasoning LLMs, I discussed a finer categorization into four categories, as summarized in the figure below.

Methods 2-4 in the figure above typically produce models that generate longer responses because they include intermediate steps and explanations in their outputs. Since inference costs scale with response length (e.g., a response twice as long requires twice the compute), these training approaches are inherently linked to inference scaling. However, in this section on inference-time compute scaling, I focus specifically on techniques that explicitly regulate the number of generated tokens, whether through additional sampling strategies, self-correction mechanisms, or other methods.

In this article, I focus on the interesting new research papers and model releases focused on scaling inference-time compute scaling that followed after the DeepSeek R1 release on January 22nd, 2025. (Originally, I wanted to cover methods from all categories in this article, but due to the excessive length, I decided to release a separate article focused on train-time compute methods in the future.)

Before we look into Inference-time compute scaling methods and the different areas of progress on the reasoning model with a focus on the inference-time compute scaling category, let me at least provide a brief overview of all the different categories.

1. Inference-time compute scaling

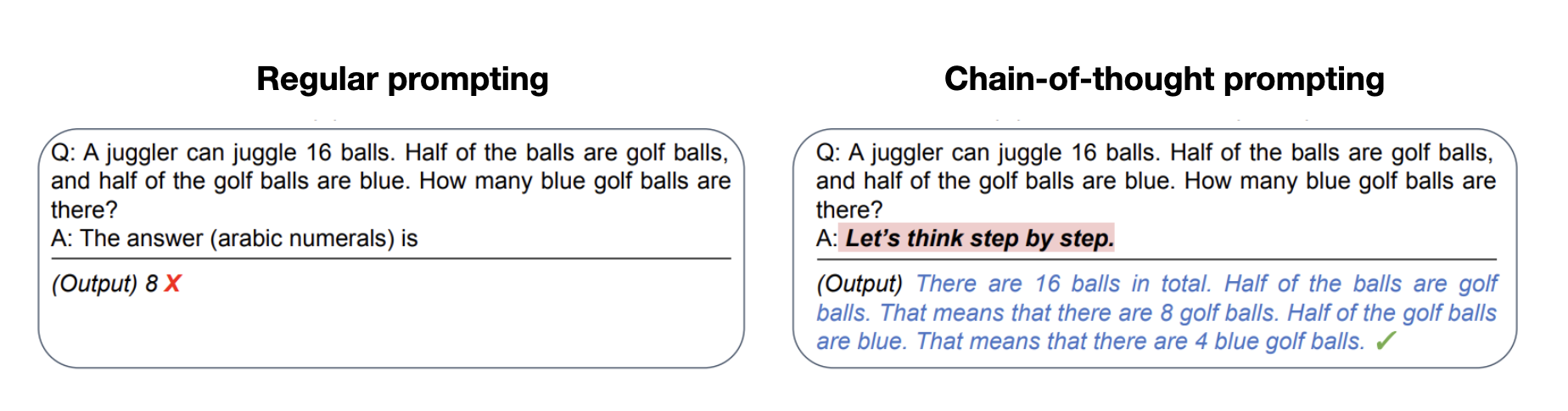

This category includes methods that improve model reasoning capabilities at inference time without training or modifying the underlying model weights. The core idea is to trade off increased computational resources for improved performance, which helps with making even fixed models more capable through techniques such as chain-of-thought reasoning, and various sampling procedures.

While I categorize inference-time compute scaling separately to focus on methods in this context, it is important to note that this technique can be applied to any LLM. For example, OpenAI developed its o1 model using reinforcement learning and then additionally leveraged inference-time compute scaling. Interestingly, as I discussed in my previous article on reasoning models (Understanding Reasoning LLMs), the DeepSeek R1 paper explicitly categorized common inference-time scaling methods (such as Process Reward Model-based and Monte Carlo Tree Search-based approaches) under “unsuccessful attempts.” This suggests that DeepSeek did not explicitly use these techniques beyond the R1 model’s natural tendency to generate longer responses, which serves as an implicit form of inference-time scaling over the V3 base model. However, since explicit inference-time scaling is often implemented at the application layer rather than within the LLM itself, DeepSeek acknowledged that they could easily incorporate it into the R1 deployment or application.

2. Pure reinforcement learning

This approach focuses solely on reinforcement learning (RL) to develop or improve reasoning capabilities. It typically involves training models with verifiable reward signals from math or coding domains. While RL allows models to develop more strategic thinking and self-improvement capabilities, it comes with challenges such as reward hacking, instability, and high computational costs.

3. Reinforcement learning and supervised fine-tuning

This hybrid approach combines RL with supervised fine-tuning (SFT) to achieve more stable and generalizable improvements than pure RL. Typically, a model is first trained with SFT on high-quality instruction data and then further refined using RL to optimize specific behaviors.

4. Supervised fine-tuning and model distillation

This method improves the reasoning capabilities of a model by instruction fine-tuning it on high-quality labeled datasets (SFT). If this high-quality dataset is generated by a larger LLM, then this methodology is also referred to as “knowledge distillation” or just “distillation” in LLM contexts. However, note that this differs slightly from traditional knowledge distillation in deep learning, which typically involves training a smaller model using not only the outputs (labels) but also the logits of a larger teacher model.

Inference-time compute scaling methods

The previous section already briefly summarized inference-time compute scaling. Before discussing the recent research in this category, let me describe the inference-time scaling in a bit more detail.

Inference-time scaling improves an LLM’s reasoning by increasing computational resources (“compute”) during inference. The idea why this can improve reasoning can be given with a simple analogy: humans give better responses when given more time to think, and similarly, LLMs can improve with techniques that encourage more “thought” during generation.

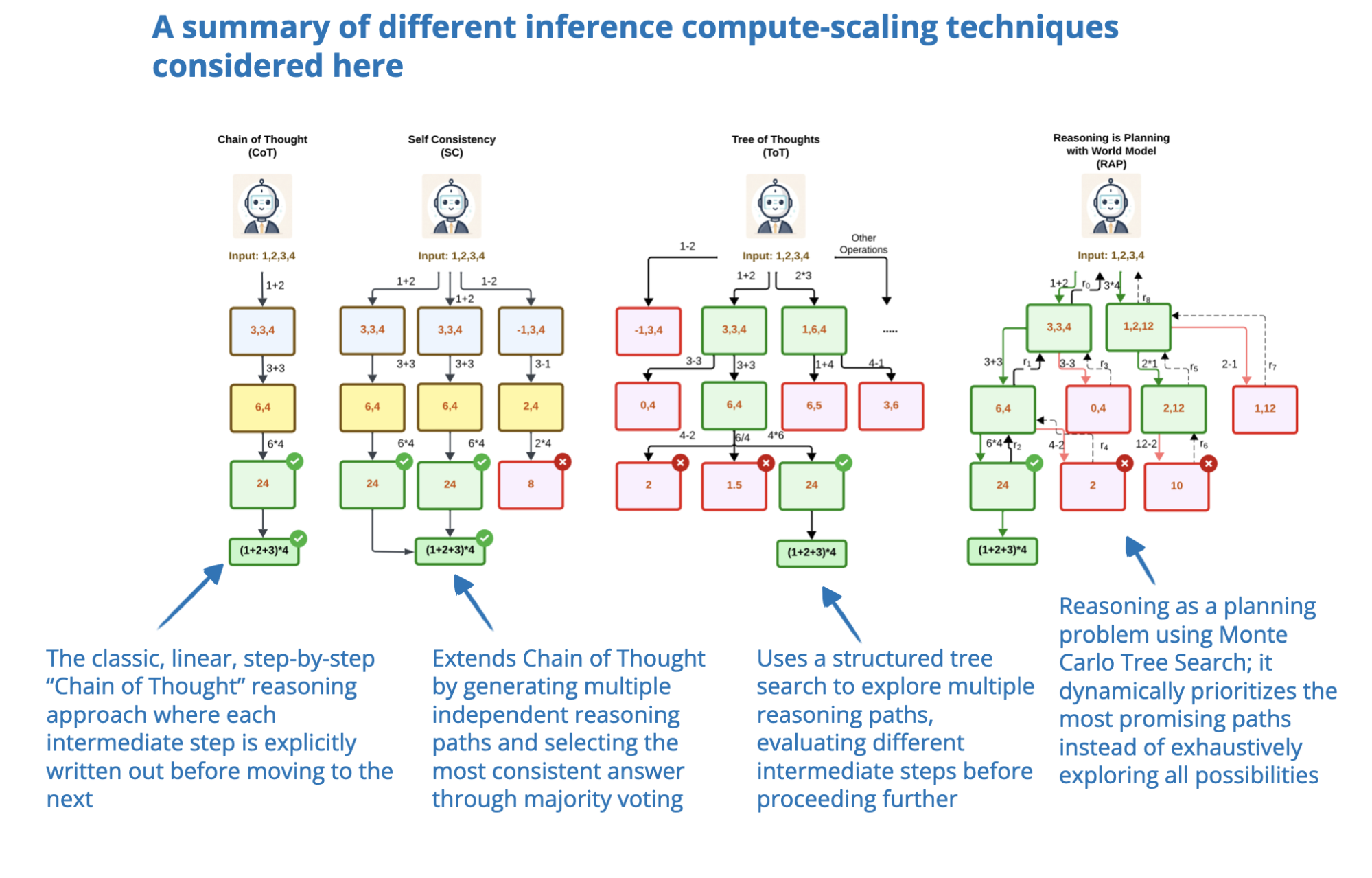

One approach here is prompt engineering, such as chain-of-thought (CoT) prompting, where phrases like “think step by step” guide the model to generate intermediate reasoning steps. This improves accuracy on complex problems but is unnecessary for simple factual queries. Since CoT prompts generate more tokens, they effectively make inference more expensive.

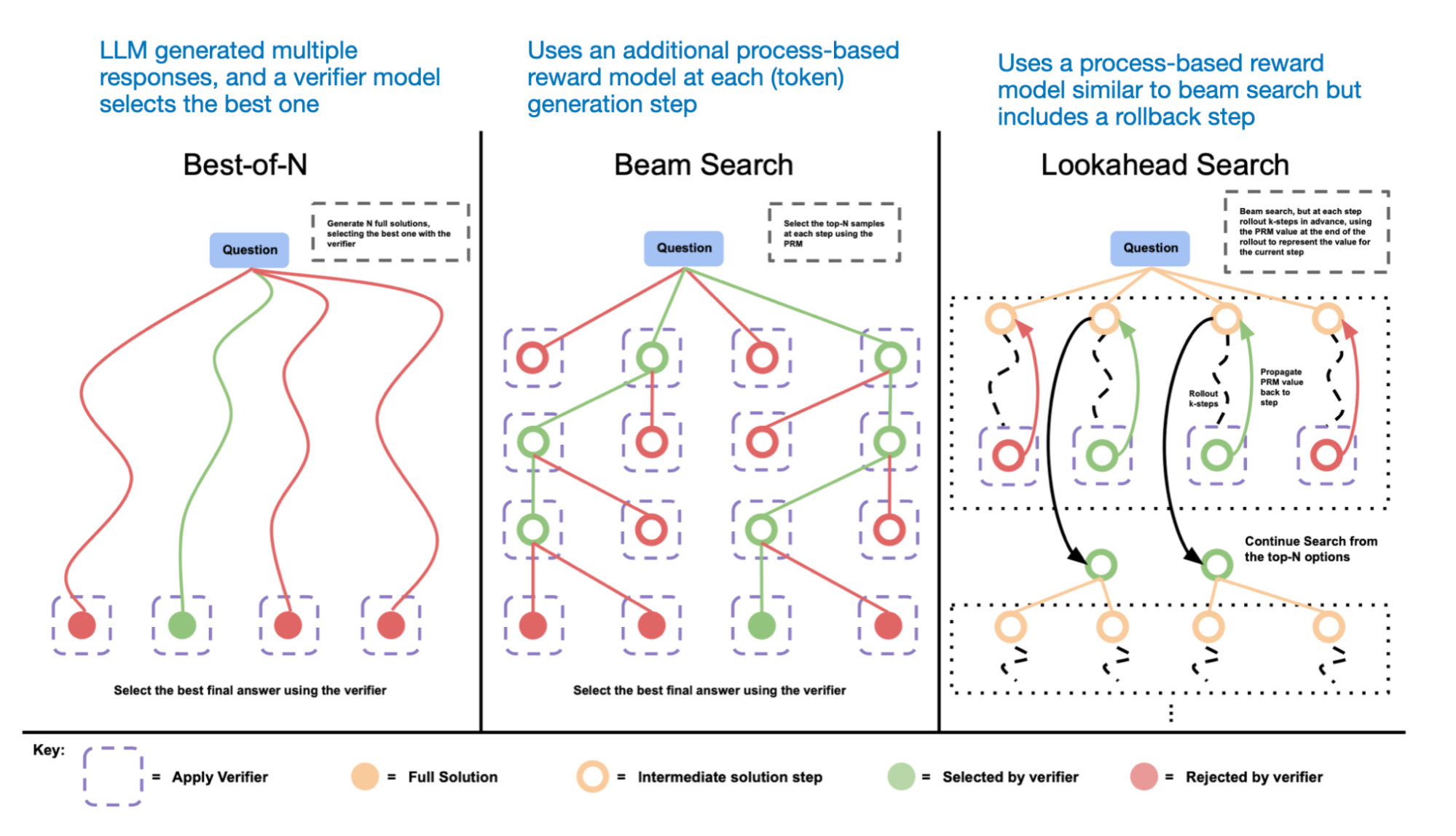

Another method involves voting and search strategies, such as majority voting or beam search, which refine responses by selecting the best output.

1. “s1: Simple test-time scaling”

The remainder of this article will be focused on the recent research advances in the inference-time scaling category for improving reasoning capabilities of LLMs. Let me start with a more detailed discussion of a paper that serves as an example of inference-time scaling.

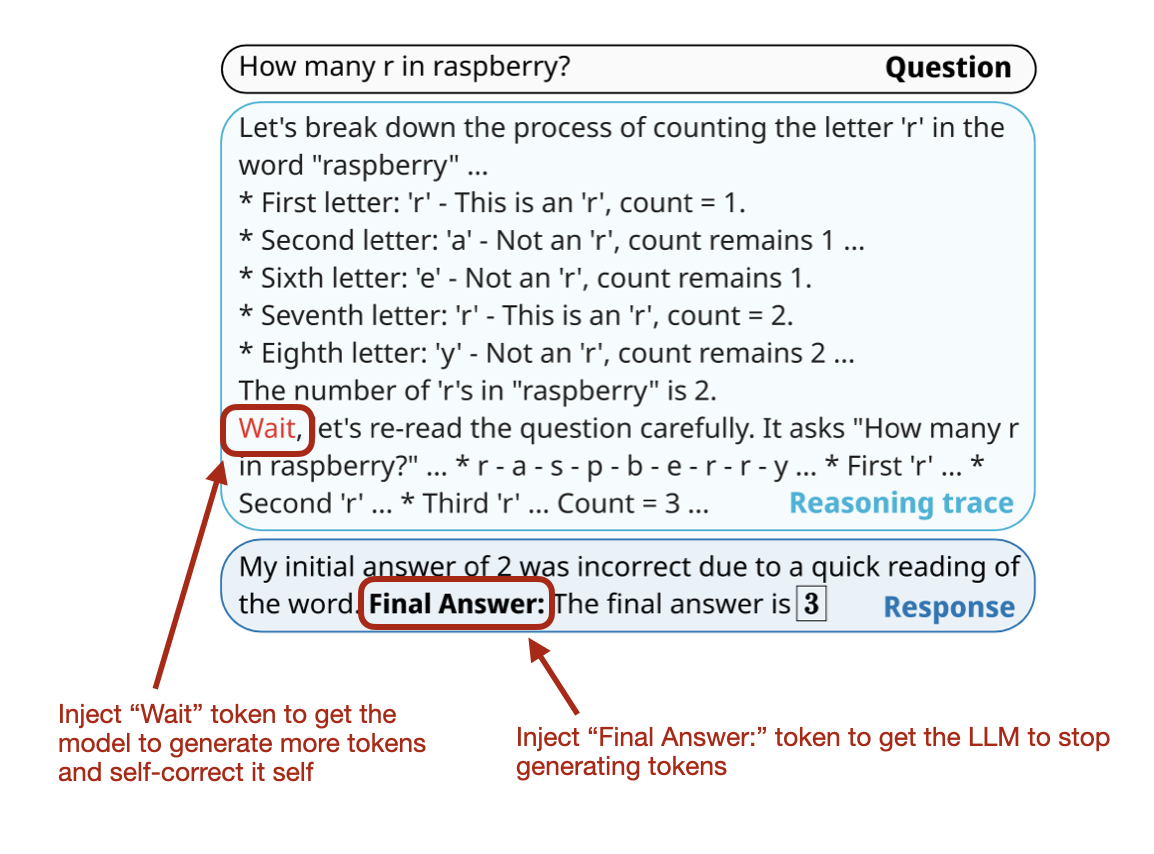

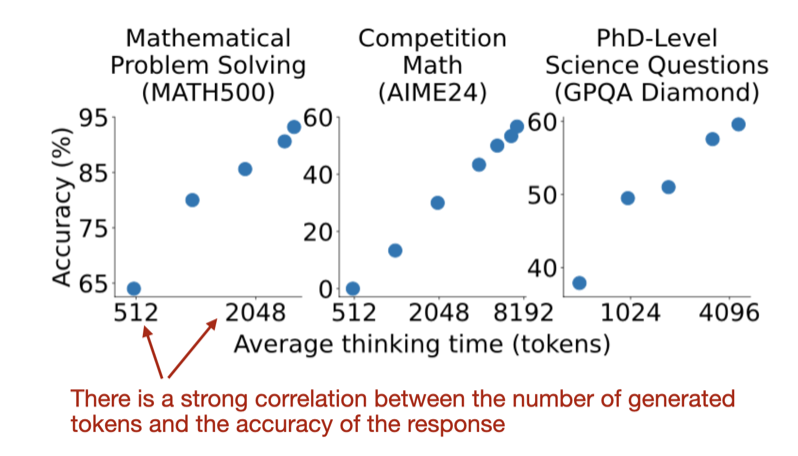

So, one of the interesting recent research papers in this category is s1: Simple Test-Time Scaling (31 Jan, 2025), which introduces so-called “wait” tokens, which can be considered as a more modern version of the aforementioned “think step by step” prompt modification.

Note that this involves supervised finetuning (SFT) to generate the initial model, so it’s not a pure inference-time scaling approach. However, the end goal is actively controlling the reasoning behavior through inference-time scaling; hence, I considered this paper for the “1. Inference-time compute scaling” category.

In short, their approach is twofold:

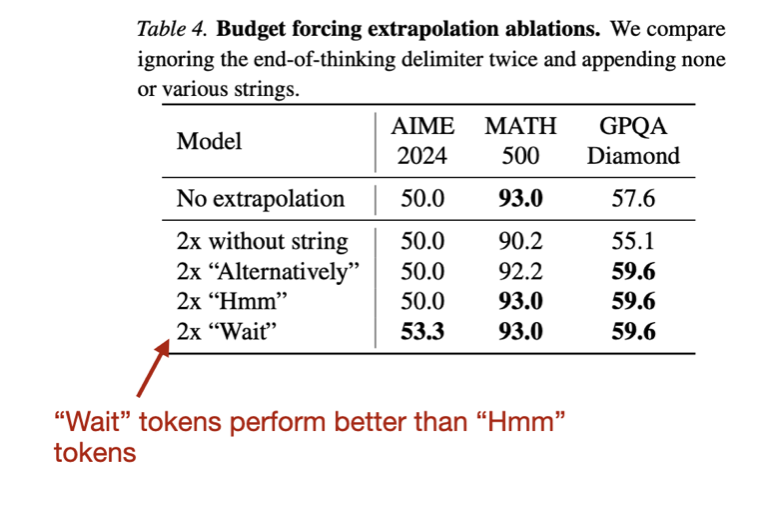

Budget forcing can be seen as a sequential inference scaling technique because it still generates one token at a time (but just more of it). In contrast, we have parallel techniques like majority voting, which aggregate multiple independent completions.

They found their budget-forcing method more effective than other inference-scaling techniques I’ve discussed, like majority voting. If there’s something to criticize or improve, I would’ve liked to see results for more sophisticated parallel inference-scaling methods, like beam search, lookahead search, or the best compute-optimal search described in Google’s Scaling LLM Test-Time Compute Optimally Can Be More Effective Than Scaling Model Parameters paper last year. Or even a simple comparison with a classic sequential method like chain-of-thought prompting (“Think step by step”).

Anyway, it’s a really interesting paper and approach!

PS: Why “Wait” tokens? My guess is the researchers were inspired by the “Aha moment” figure in the DeepSeek-R1 paper, where researchers saw LLMs coming up with something like “Wait, wait. Wait. That’s an aha moment I can flag here.” which showed that pure reinforcement learning can induce reasoning behavior in LLMs.

Interestingly, they also tried other tokens like “Hmm” but found that “Wait” performed slightly better.

Other noteworthy research papers on inference-time compute scaling

Since it’s been a very active month on the reasoning model research front, I need to keep the summaries of other papers relatively brief to manage a reasonable length for this article. Hence, below are brief summaries of other interesting research articles related to inference-time compute scaling, sorted in ascending order by publication date.

As mentioned earlier, not all of these articles fall neatly into the inference-time compute scaling category, as some of them also involve specific training. However, these papers have in common that controlling inference-time compute is a specific mechanism of action. (Many distilled or SFT methods that I will cover in upcoming articles will lead to longer responses, which can be seen as a form of inference-time compute scaling. However, they do not actively control the length during inference, which makes these methods different from those covered here.)

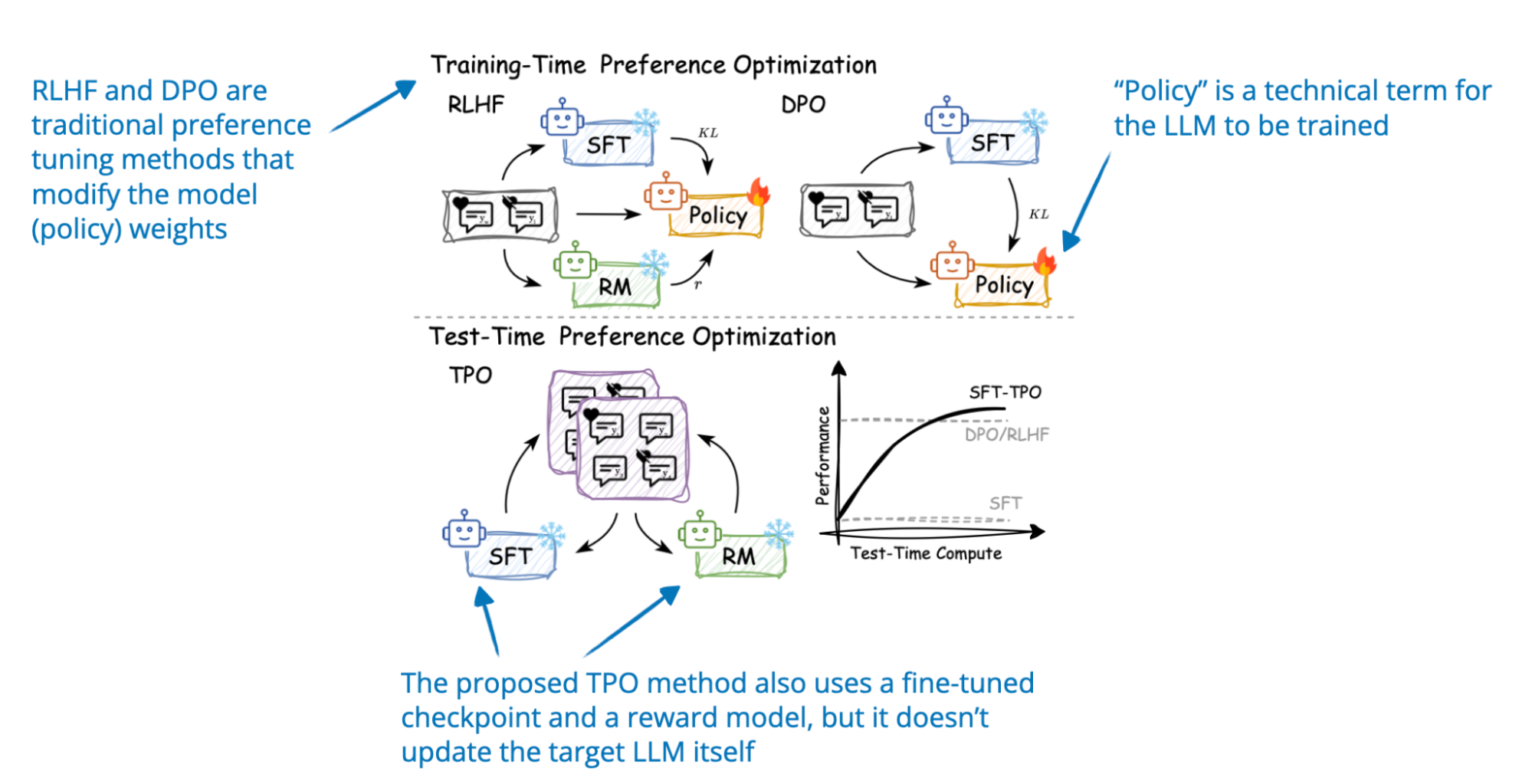

2. Test-Time Preference Optimization

📄 22 Jan, Test-Time Preference Optimization: On-the-Fly Alignment via Iterative Textual Feedback, https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.12895

Test-time Preference Optimization (TPO) is an iterative process that aligns LLM outputs with human preferences during inference (this is without altering its underlying model weights). In each iteration, the model:

By doing steps 1-4 iteratively, the model refines its original responses.

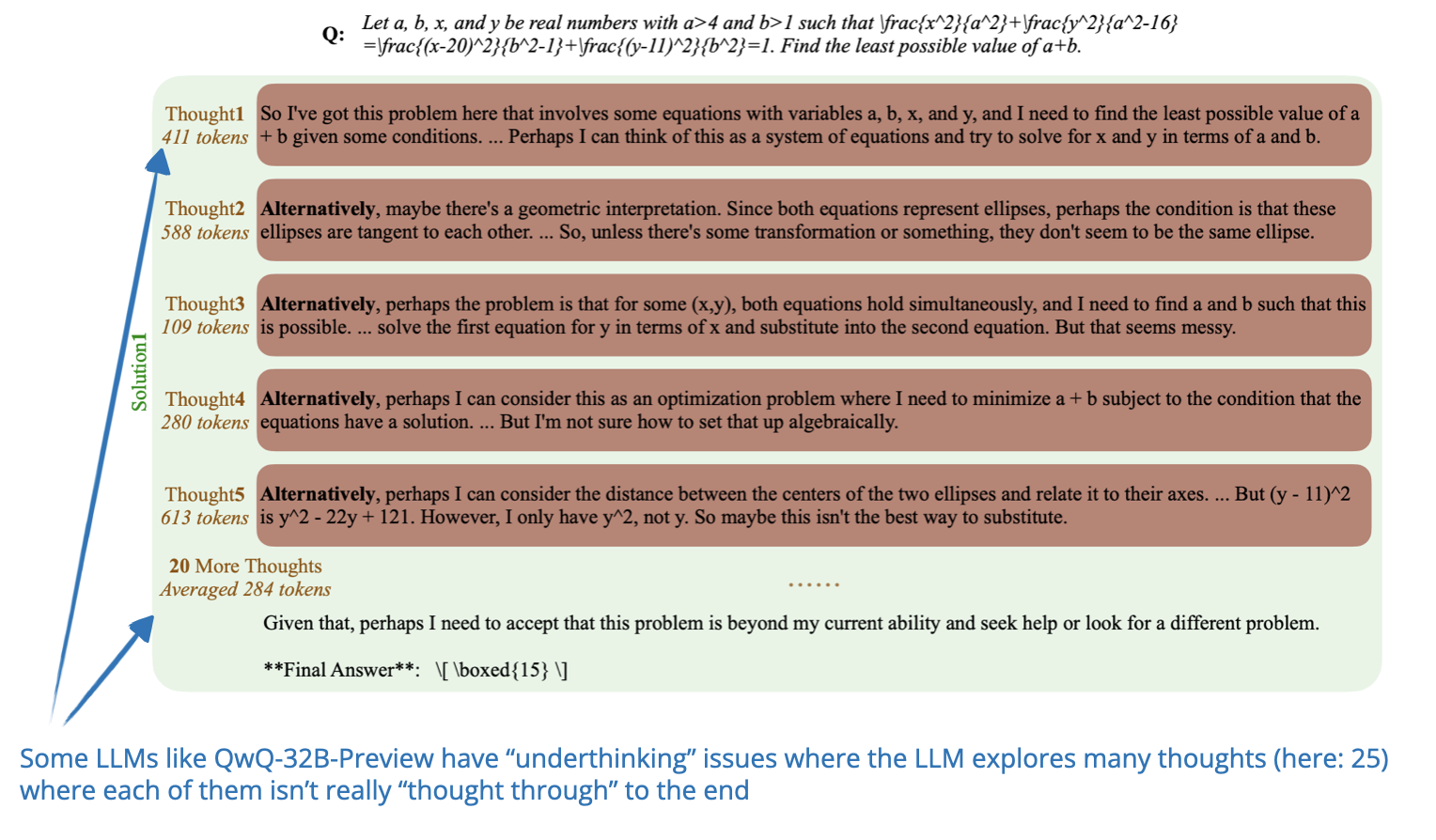

3. Thoughts Are All Over the Place

📄 30 Jan, Thoughts Are All Over the Place: On the Underthinking of o1-Like LLMs, https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.18585

The researchers explore a phenomenon called “underthinking”, where reasoning models frequently switch between reasoning paths instead of fully focusing on exploring promising ones, which lowers the problem solving accuracy.

To address this “underthinking” issue, they introduce a method called the Thought Switching Penalty (TIP), which modifies the logits of thought-switching tokens to discourage premature reasoning path transitions.

Their approach does not require model fine-tuning and empirically improves accuracy across multiple challenging test sets.

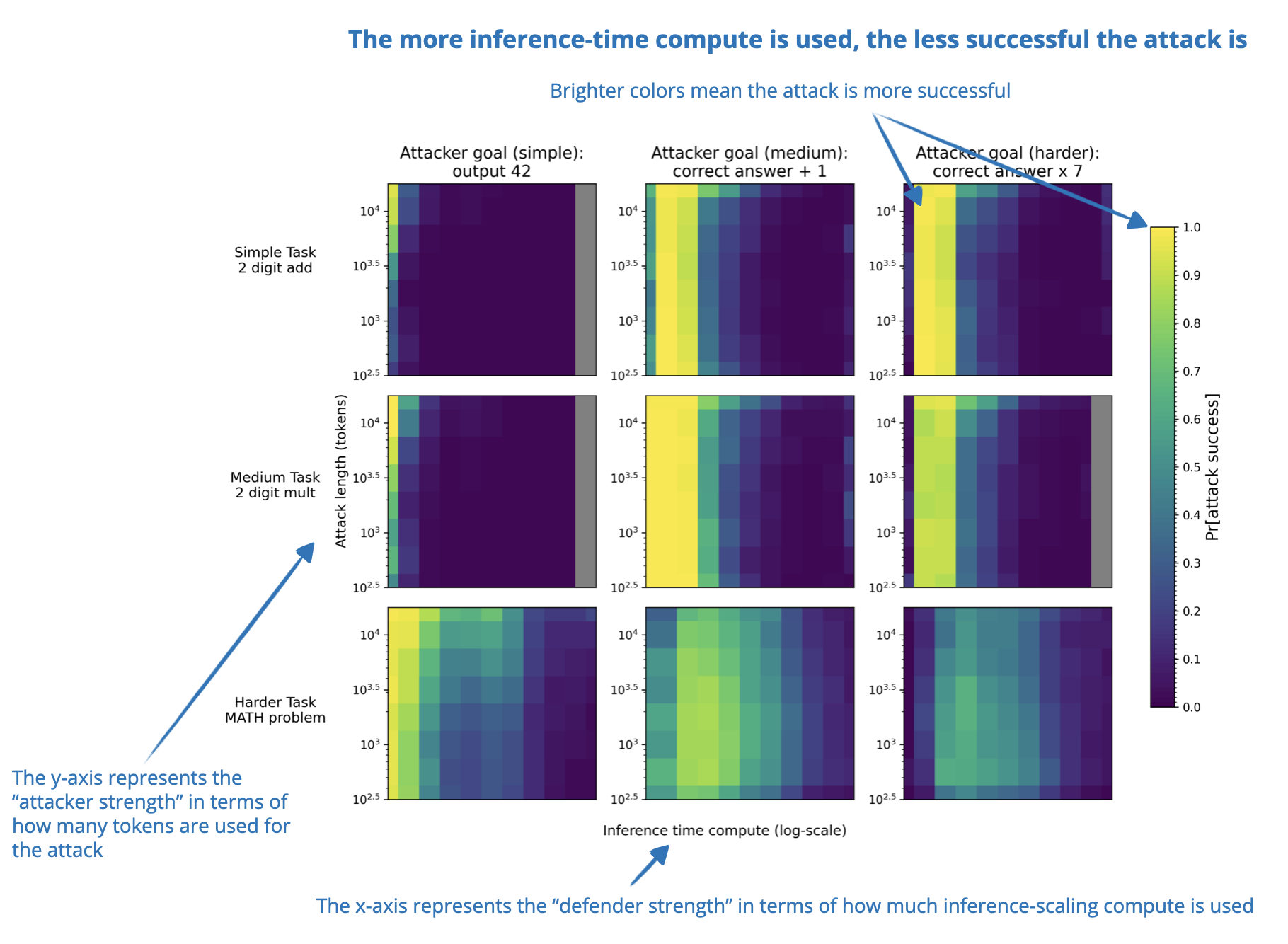

4. Trading Inference-Time Compute for Adversarial Robustness

📄 31 Jan, Trading Inference-Time Compute for Adversarial Robustness, https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.18841

Increasing inference-time compute improves the adversarial robustness of reasoning LLMs in many cases in terms of reducing the rate of successful attacks. Unlike adversarial training, this method does not need any special training or require prior knowledge of specific attack types.

However, there are some important exceptions. For example, the improvements in settings involving policy ambiguities or loophole exploitation are limited. Additionally, the reasoning-improved robustness increases can be reduced by new attack strategies such as “Think Less” and “Nerd Sniping”.

So, while these findings suggest that scaling inference-time compute can improve LLM safety, this alone is not a complete solution to adversarial robustness.

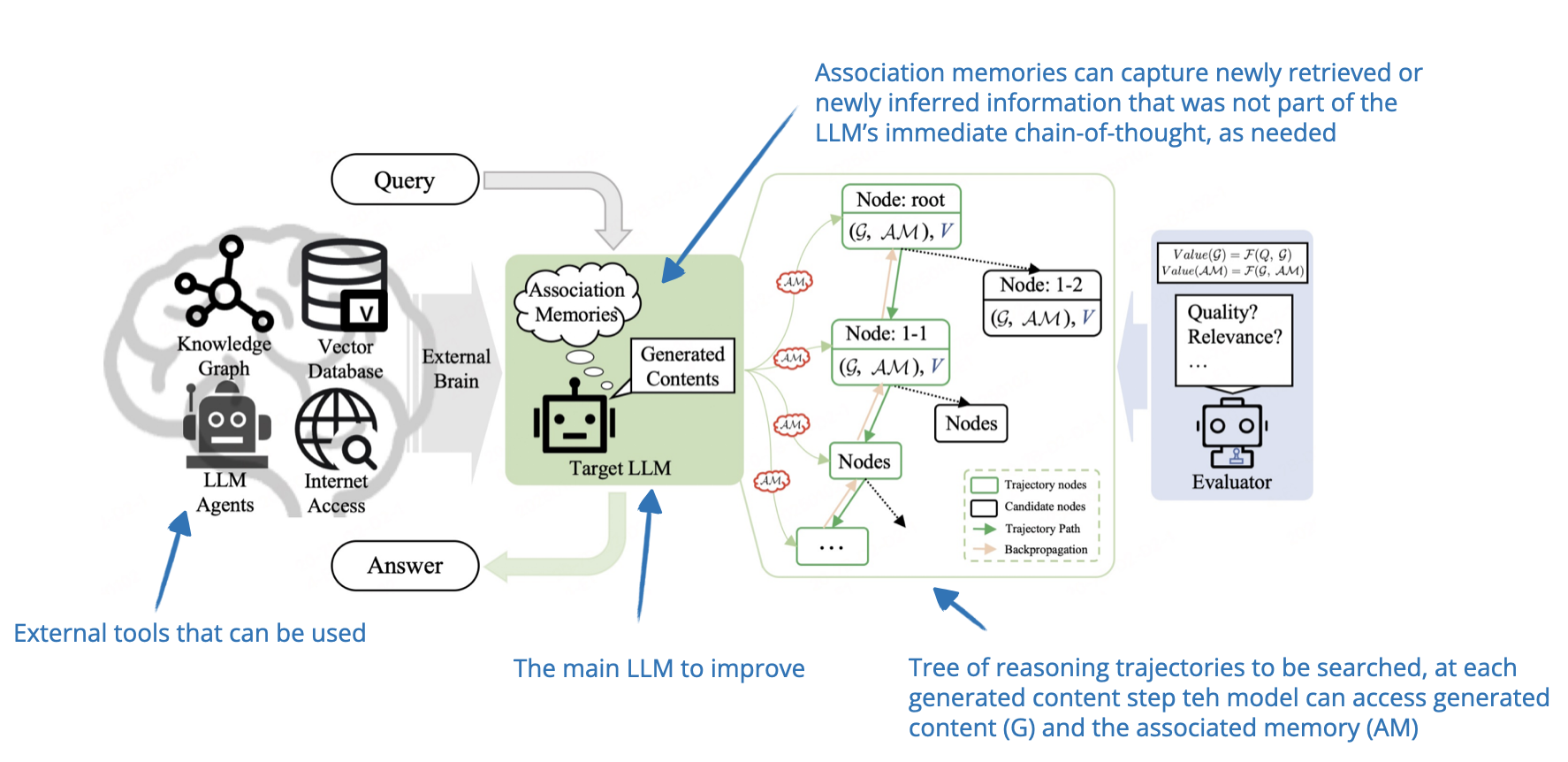

5. Chain-of-Associated-Thoughts

📄 4 Feb, CoAT: Chain-of-Associated-Thoughts Framework for Enhancing Large Language Models Reasoning, https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.02390

The researchers combine classic Monte Carlo Tree Search inference-time scaling with an “associative memory” that serves as the LLM’s knowledge base during the exploration of reasoning pathways. Using this so-called associative memory, it’s easier for the LLM to consider earlier reasoning pathways and use dynamically involving information during the response generation.

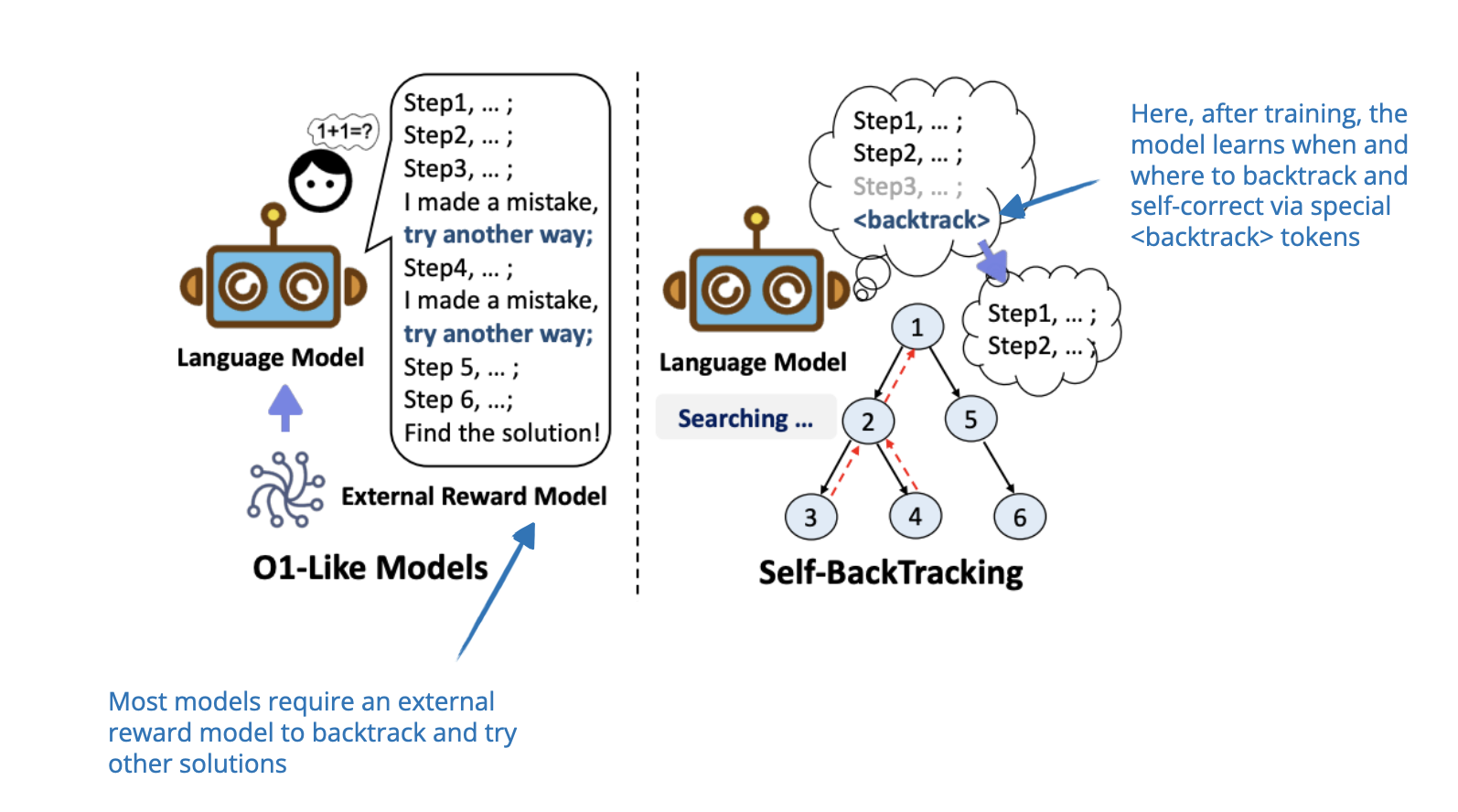

6. Step Back to Leap Forward

📄 6 Feb, Step Back to Leap Forward: Self-Backtracking for Boosting Reasoning of Language Models, https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.04404

This paper proposes a self-backtracking mechanism that allows LLMs to improve their reasoning by learning when and where to backtrack during training and inference. While training involves teaching the model to recognize and correct suboptimal reasoning paths using a

What’s unique is that this exploration does not require without relying on external reward models (unlike the search-based methods that use a process-reward-based model that I mentioned at the beginning of the “1. Inference-time compute scaling methods” section in this article).

I added this paper here as it’s heavily focused on the proposed backtracking inference-time scaling method, which improves reasoning by dynamically adjusting search depth and breadth rather than fundamentally altering the training paradigm (although, the training with

7. Scaling up Test-Time Compute with Latent Reasoning

📄 7 Feb, Scaling up Test-Time Compute with Latent Reasoning: A Recurrent Depth Approach, https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.05171

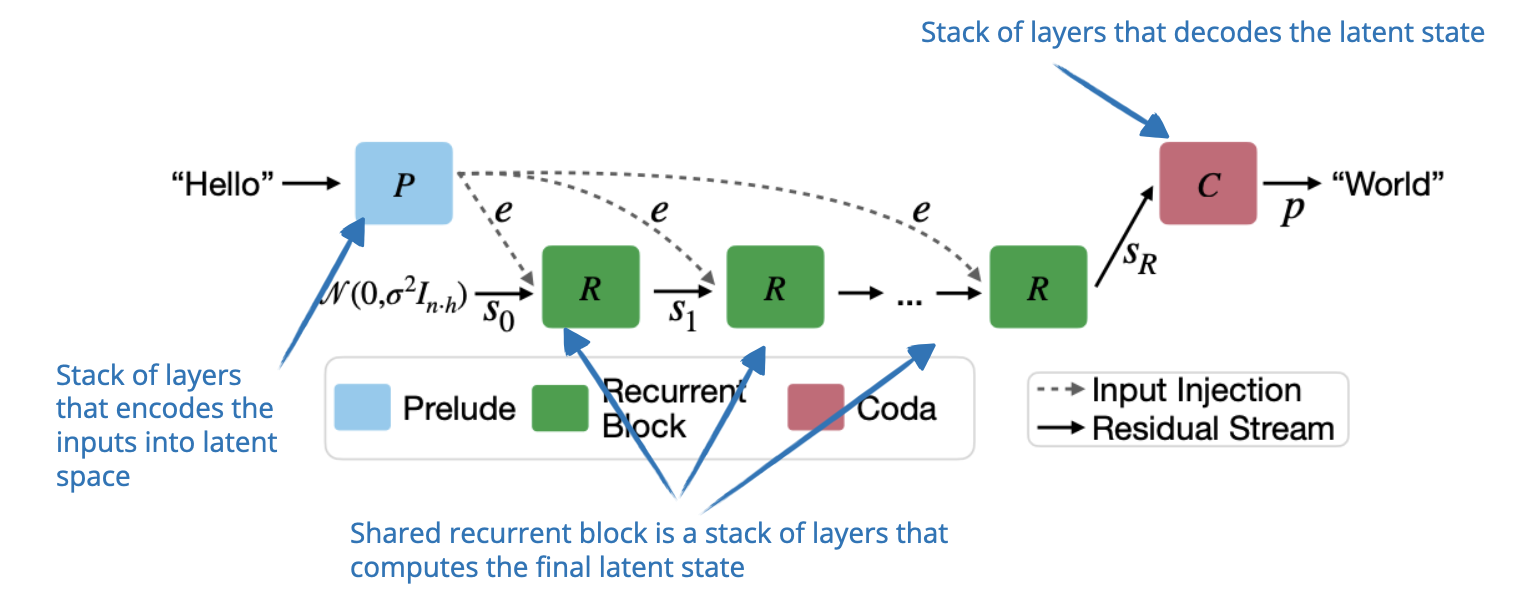

Instead of improving reasoning by generating more tokens, the researchers propose a model that scales inference-time compute by iterating over a recurrent depth block in latent space. This block functions like a hidden state in RNNs, which allows the model to refine its reasoning without requiring longer token outputs.

However, a key drawback is the lack of explicit reasoning steps, which are (in my opinion) useful for human interpretability and a major advantage of chain-of-thought methods.

8. Can a 1B LLM Surpass a 405B LLM?

📄 10 Feb, Can 1B LLM Surpass 405B LLM? Rethinking Compute-Optimal Test-Time Scaling, https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.06703

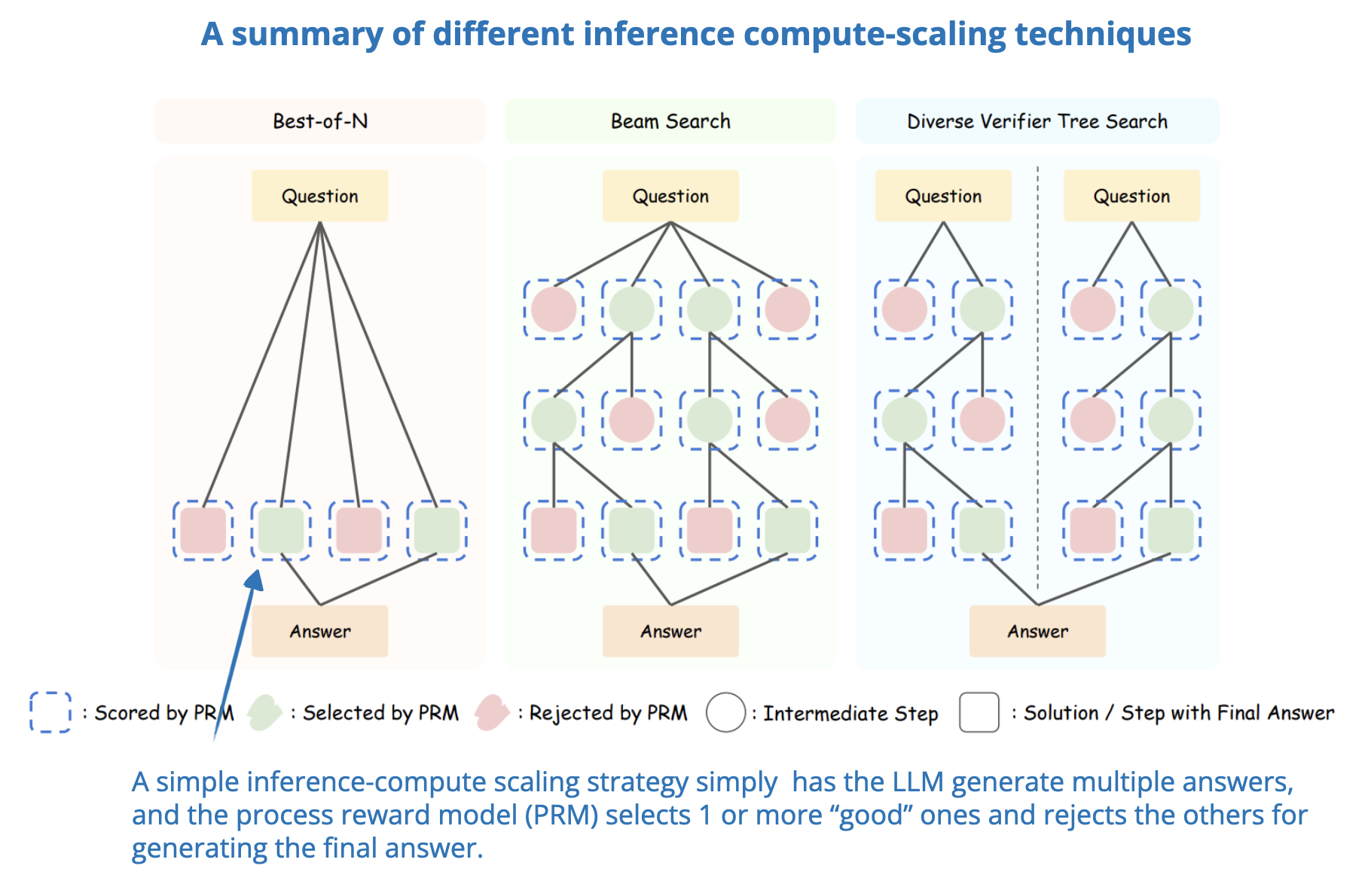

Many inference-time scaling techniques depend on sampling, which requires a Process Reward Model (PRM) to select the best solution. This paper systematically analyzes how inference-time compute scaling interacts with PRMs and problem difficulty.

The researchers develop a compute-optimal scaling strategy that adapts to the choice of PRM, policy model, and task complexity. Their results show that with the right inference-time scaling approach, a 1B parameter model can outperform a 405B Llama 3 model that lacks inference-time scaling.

Similarly, they show how a 7B model with inference-time scaling surpasses DeepSeek-R1 while maintaining higher inference efficiency.

These findings highlight how inference-time scaling can significantly improve LLMs, where small LLMs, with the right inference compute budget, can outperform much larger models.

9. Learning to Reason from Feedback at Test-Time

📄 16 Feb, Learning to Reason from Feedback at Test-Time, https://www.arxiv.org/abs/2502.12521

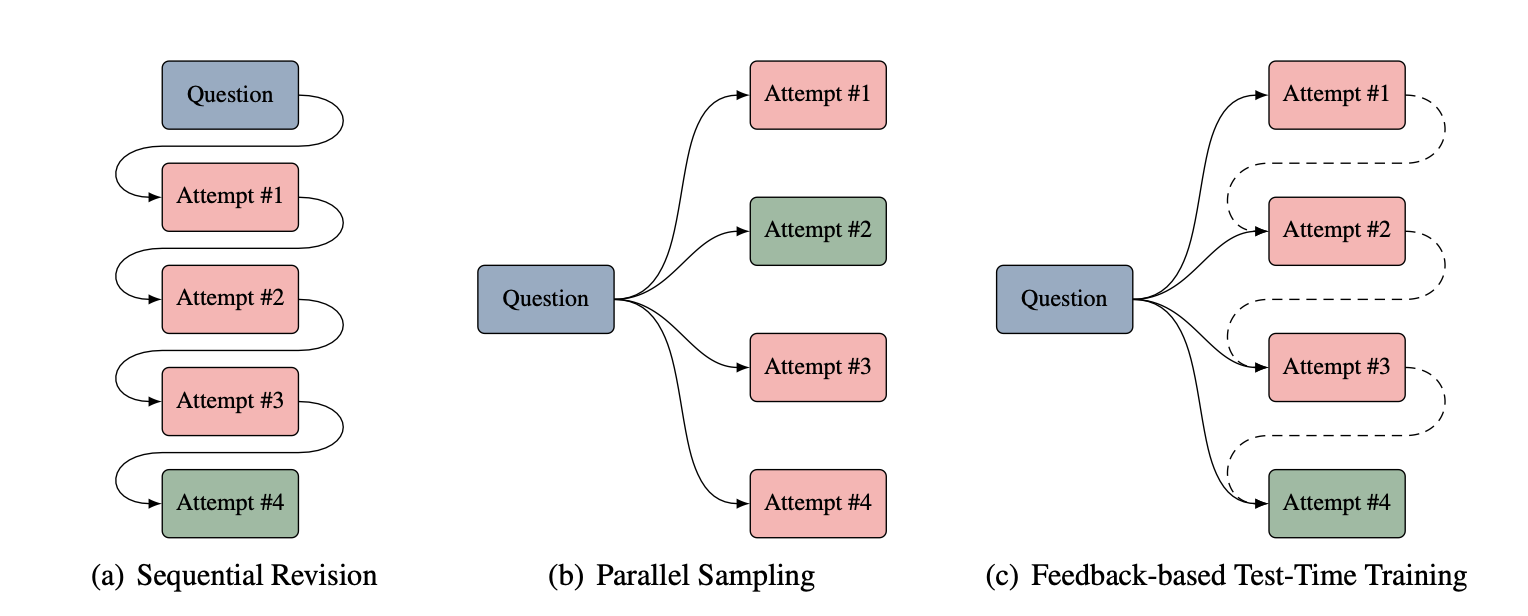

It’s a bit hard to classify this as either an inference-time or training-time method, because it optimizes the LLM, changing its weight parameters, at inference-time.

So, this paper explores a way to make LLMs learn from their mistakes during inference time without having to store failed attempts in the prompt (which gets expensive). Instead of the usual method of refining answers by adding previous attempts to the context (sequential revision) or blindly generating new answers (parallel sampling), this approach updates the model’s weights at inference time.

To do this, the authors introduce OpTune, a small, trainable optimizer that updates the model’s weights based on the mistakes it made in a previous attempt. This means the model remembers what it did wrong without needing to keep the incorrect answer in the prompt/context.

10. Inference-Time Computations for LLM Reasoning and Planning

📄 18 Feb, Inference-Time Computations for LLM Reasoning and Planning: A Benchmark and Insights, https://www.arxiv.org/abs/2502.12521

This paper benchmarks various inference-time compute scaling techniques for reasoning and planning tasks with a focus on analyzing their trade-offs between computational cost and performance.

The authors evaluate multiple techniques—such as Chain-of-Thought, Tree-of-Thought, and Reasoning as Planning across eleven tasks spanning arithmetic, logical, commonsense, algorithmic reasoning, and planning.

The main finding is that while scaling inference-time computation can improve reasoning, no single technique consistently outperforms others across all tasks.

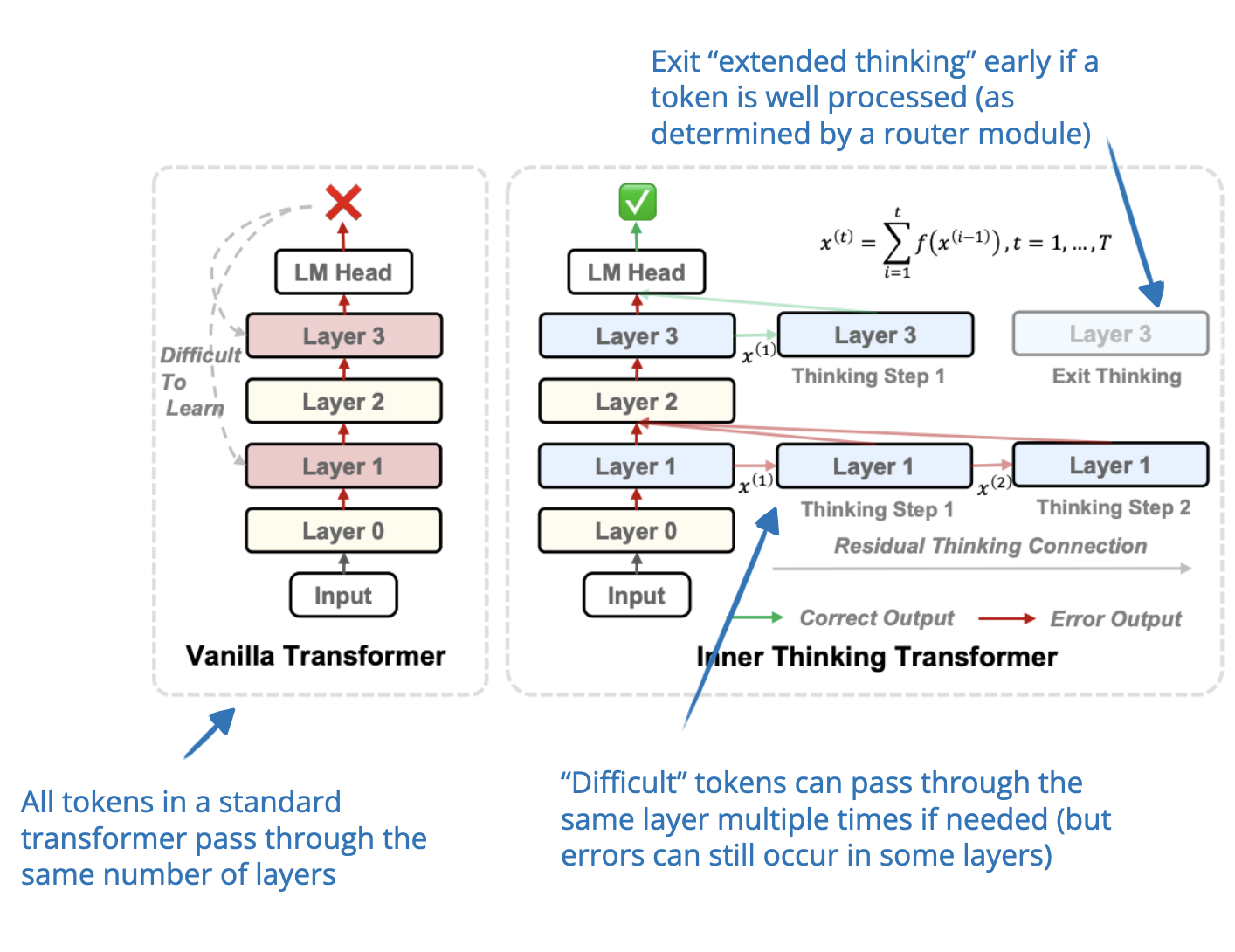

11. Inner Thinking Transformer

📄 19 Feb, Inner Thinking Transformer: Leveraging Dynamic Depth Scaling to Foster Adaptive Internal Thinking, https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.13842

The Inner Thinking Transformer (ITT) dynamically allocates more compute during inference. Instead of using a fixed depth (= using same number of layers) for all tokens as in standard transformer-based LLMs, ITT employs Adaptive Token Routing to allocate more compute to difficult tokens. These difficult tokens pass through the same layer multiple times to undergo additional processing, which increases the inference-compute budget for these difficult tokens.

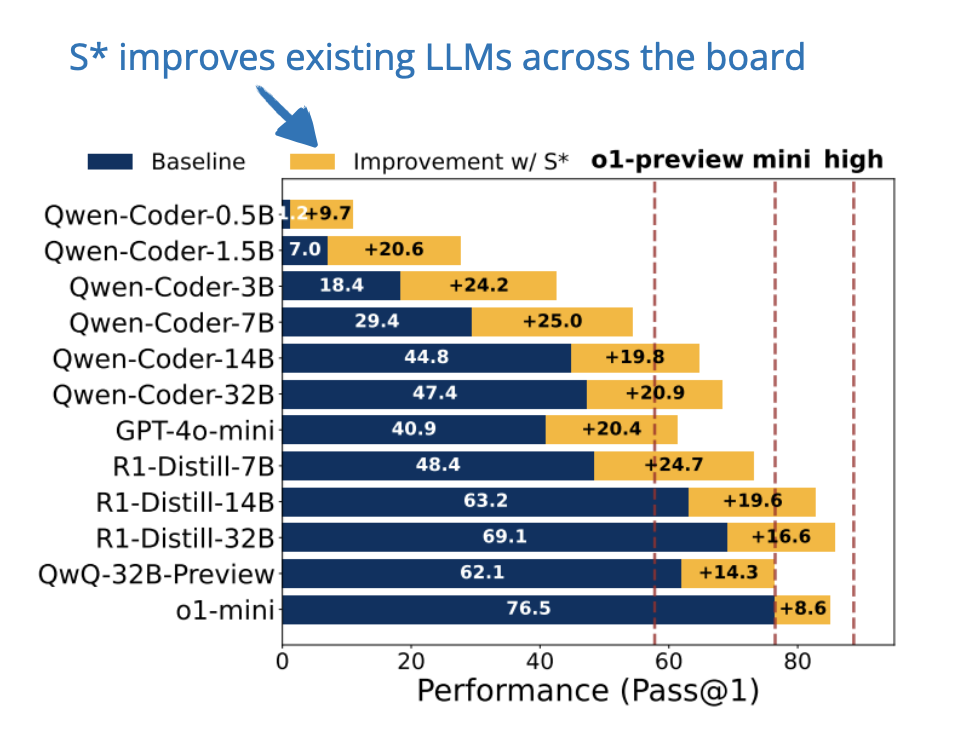

12. Test Time Scaling for Code Generation

📄 20 Feb, S*: Test Time Scaling for Code Generation, https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.14382

Inference-time scaling can be achieved by parallel scaling (generating multiple answers), sequential scaling (iteratively refining answers), or both as described in the Google paper from Summer 2024 (Scaling LLM Test-Time Compute Optimally can be More Effective than Scaling Model Parameters).

S* is a test-time compute scaling method designed specifically for code generation that improves both parallel scaling (generating multiple solutions) and sequential scaling (iterative debugging).

The approach operates in two stages:

Stage 1: Generation

The model generates multiple code solutions and iteratively refines them using execution results and test cases provided in the problem prompt.

Think of this like a coding competition where a model submits solutions, runs tests, and fixes mistakes:

-

The model generates multiple candidate solutions.

-

Each solution is executed on public test cases (predefined input-output pairs).

-

If a solution fails (incorrect output or crashes), the model analyzes the execution results (errors, outputs) and modifies the code to improve it.

-

This refinement process continues iteratively until the model finds solutions that pass the test cases.

For example, suppose the model is asked to implement a function is_even(n) that returns True for even numbers and False otherwise.

The model’s first attempt might be:

def is_even(n):

return n % 2 # ❌ Incorrect: should be `== 0`

The model tests this implementation with public test cases:

Input Expected Model Output Status

is_even(4) True False ❌ Fail

is_even(3) False True ❌ Fail

After reviewing the results, the model realizes that 4 % 2 returns 0, not True, so it modifies the function:

def is_even(n):

return n % 2 == 0 # ✅ Corrected

Now the function passes all public tests, completing the debugging phase.

Stage 2: Selection

Once multiple solutions have passed public tests, the model must choose the best one (if possible). Here, S* introduces adaptive input synthesis to avoid random picking:

-

The model compares two solutions that both pass public tests.

-

It asks itself: “Can I generate an input that will reveal a difference between these solutions?”

-

It creates a new test input and runs both solutions on it.

-

If one solution produces the correct output while the other fails, the model selects the better one.

-

If both solutions behave identically, the model randomly picks one.

For example, consider two different implementations of is_perfect_square(n):

import math

def is_perfect_square_A(n):

return math.isqrt(n) ** 2 == n

def is_perfect_square_B(n):

return math.sqrt(n).is_integer()

Both pass the provided test cases for simple examples:

n = 25

print(is_perfect_square_A(n)) # ✅ True (Correct)

print(is_perfect_square_B(n)) # ✅ True (Correct)

But when the LLM generates edge cases we can see one of them fail, so the model would select the solution A in this case:

n = 10**16 + 1

print(is_perfect_square_A(n)) # ✅ False (Correct)

print(is_perfect_square_B(n)) # ❌ True (Incorrect)

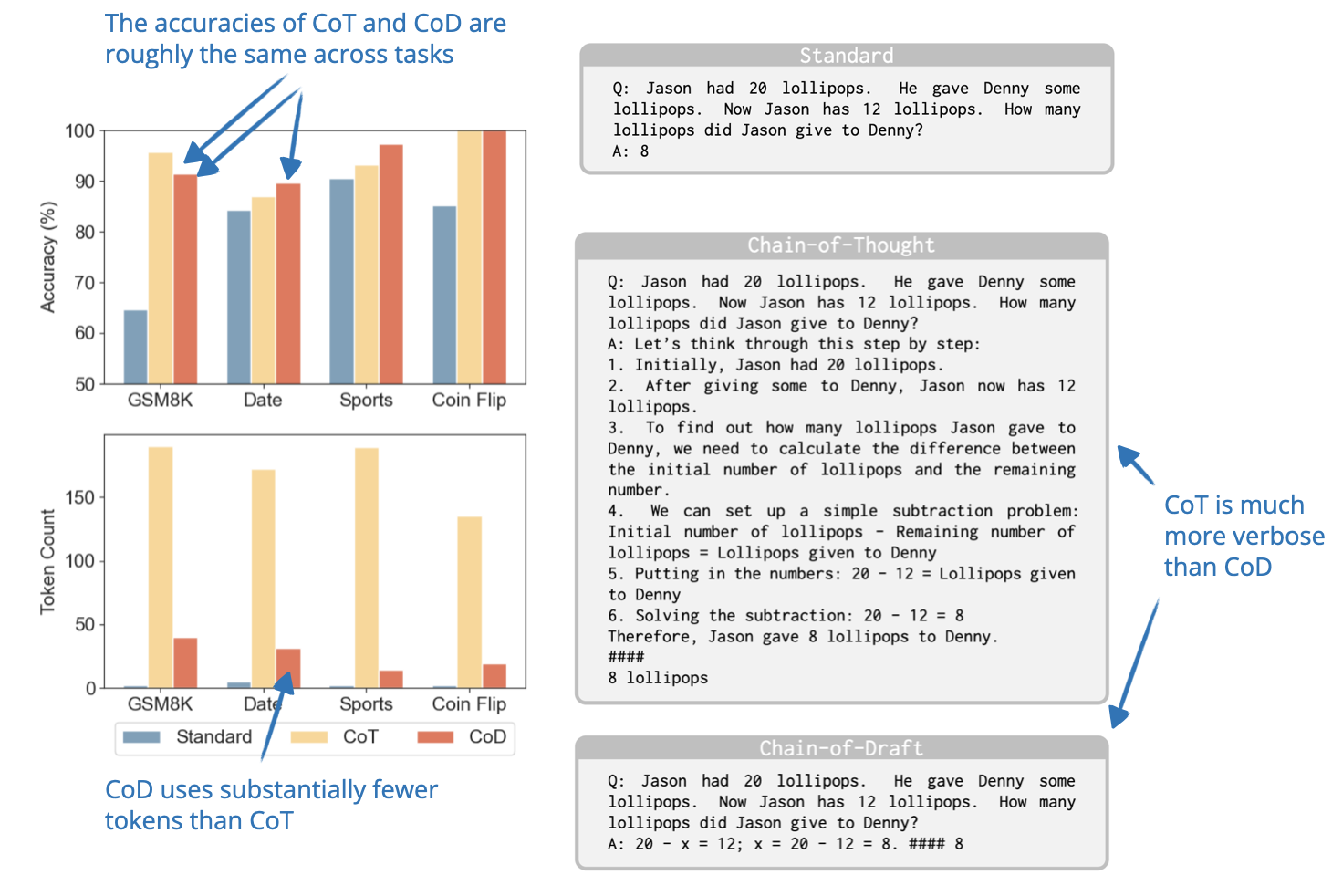

13. Chain of Draft

📄 25 Feb, Chain of Draft: Thinking Faster by Writing Less, https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.18600

The researchers observe that while reasoning LLMs often generate verbose step-by-step explanations, humans typically rely on concise drafts that capture only essential information.

Inspired by this, they propose Chain of Draft (CoD), a prompting strategy that reduces verbosity by generating minimal but informative intermediate steps. So, in a sense it’s a method for inference-time scaling that improves the efficiency of inference-time scaling through generating fewer tokens.

Looking at the results, it seems that CoD is almost as brief as standard prompting, but as accurate as Chain of Thought (CoT) prompting. As I mentioned earlier, in my opinion, one of the advantages of reasoning models is that users can read the reasoning traces to learn and to better evaluate / trust the response. CoD somewhat diminishes the advantage of CoD. However, it might come in very handy where verbose intermediate steps are not needed as it speeds up the generation while maintaining the accuracy of CoT.

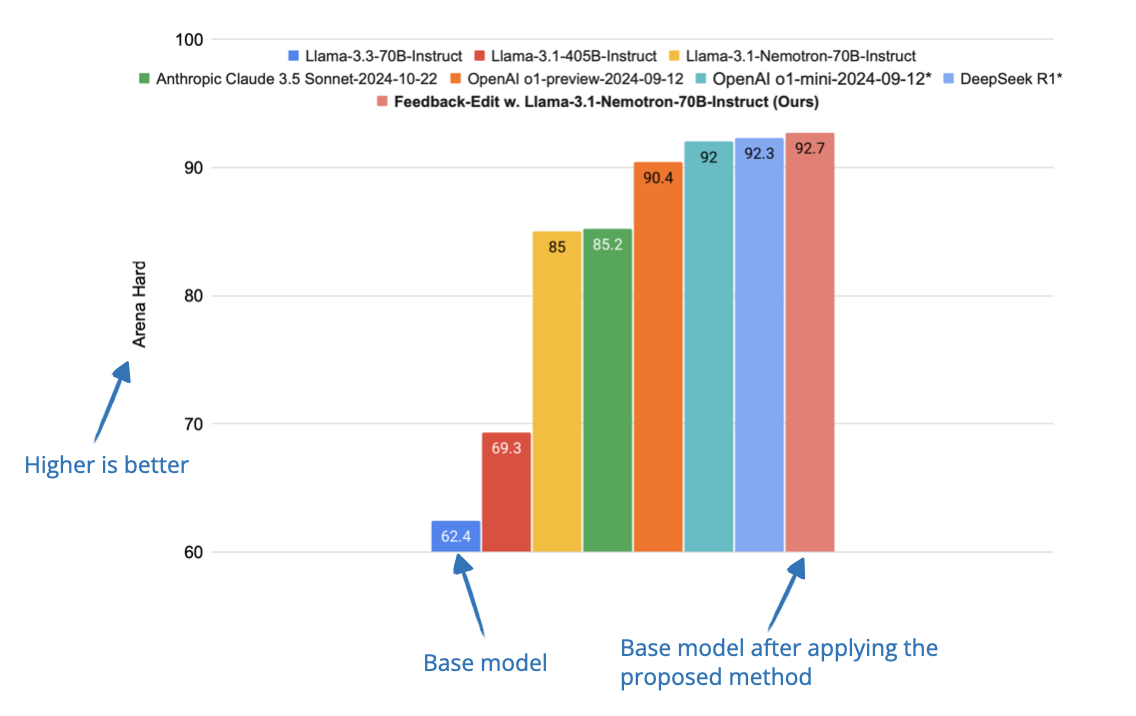

14. Better Feedback and Edit Models

📄 6 Mar, Dedicated Feedback and Edit Models Empower Inference-Time Scaling for Open-Ended General-Domain Tasks, https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.04378

Many techniques for scaling inference-time reasoning rely on tasks with verifiable answers (like math and code that can be checked), which makes them difficult to apply to open-ended tasks like writing and general problem-solving.

To address this limitation regarding verifiable answers, the researchers develop a system where one model generates an initial response, another provides feedback (“feedback model”), and a third refines the response based on that feedback (“edit model”).

They train these specialized “feedback” and “edit” models using a large dataset of human-annotated responses and feedback. These models then help improve responses by generating better feedback and making more effective edits during inference time.

Conclusion

Inference-time compute scaling has become one of the hottest research topics this year to improve the reasoning abilities of large language models without requiring modification to model weights.

The many techniques I summarized above range from simple token-based interventions like “Wait” tokens to sophisticated search and optimization-based strategies such as Test-Time Preference Optimization and Chain-of-Associated-Thoughts.

On the big-picture level, one recurring theme is that increasing compute at inference allows even relatively small models to achieve substantial improvements (on reasoning benchmarks) compared to standard approaches.

This suggests that inference strategies can help narrow the performance gap between smaller, more cost-effective models and their larger counterparts.

The cost caveat

The caveat is that inference-time scaling increases the inference costs, so whether to use a small model with substantial inference scaling or training a larger model and using it with less or no inference scaling is a math that has to be worked out based on how much use the model gets.

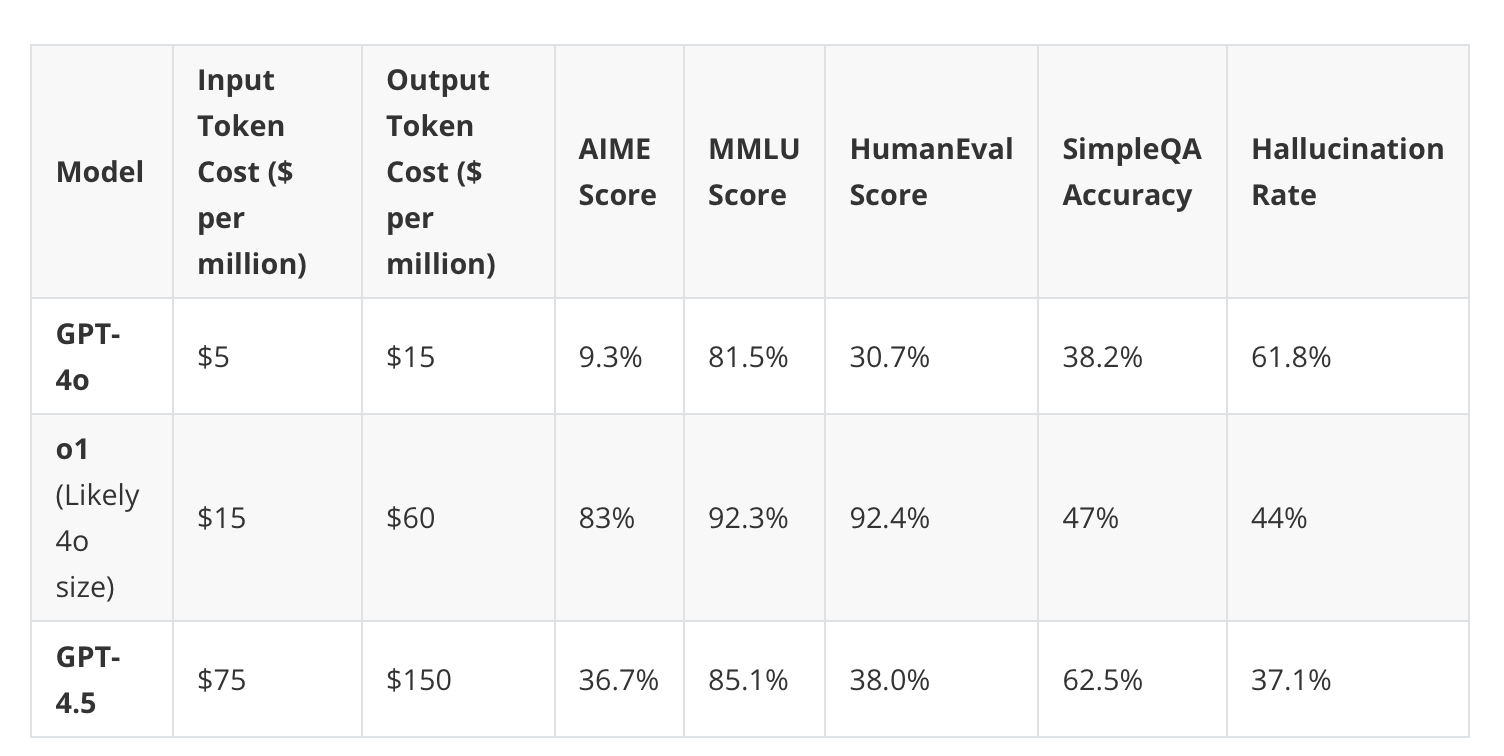

As an example, an o1 model, which uses heavy inference time scaling, is actually still slightly cheaper than a likely larger GPT-4.5 model that likely doesn’t use inference time scaling.

(It will be interesting to see how well GPT-4.5 will perform with o1- or o3-style inference-time scaling.)

Which technique?

However, inference-time compute scaling is not a silver bullet. While methods like Monte Carlo Tree Search, self-backtracking, and dynamic-depth scaling can substantially improve reasoning performance, the effectiveness also still depends on the task and difficulty. As one of the earlier papers showed, there’s no inference-time compute scaling technique that performs best across all tasks.

Additionally, many of these approaches trade off response latency for improved reasoning, and slow responses can be annoying to some users. For instance, I usually switch from o1 to GPT4o if I have simple tasks due to the faster response time.

What’s next

Looking ahead, I think we will see many more papers this year centered around the two main branches of “reasoning via inference-time compute scaling” research:

-

Research that is purely centered around developing the best possible model topping the benchmarks.

-

Research that is concerned with balancing cost and performance trade-offs across different reasoning tasks.

Either way, what’s nice about inference-time compute scaling is that it can be applied to any type of existing LLM to make it better for specific tasks.

Thinking on Demand

An interesting trend on the industry side is what I refer to as “thinking on demand”. Following the release of DeepSeek R1, it feels like companies have been rushing to add reasoning capabilities to their offerings.

An interesting development here is that most LLM providers started to add the option for users to enable or disable thinking. An interesting development is that most LLM providers now allow users to enable or disable these “thinking” features. The mechanism is not publicly shared, but it’s likely the same model with dialed-back inference-time compute scaling.

For instance, Claude 3.7 Sonnet and Grok 3 now have a “thinking” that users can enable for their model, whereas OpenAI requires users to switch between models. For example, GPT4o/4.5 and o1/o3-mini if they want to use explicit reasoning models. However, the OpenAI CEO mentioned that GPT4.5 will likely be their last model, which doesn’t explicitly have a reasoning or “thinking” mode. On the open-source side, even IBM added an explicit “thinking” toggle to their Granite models.

Overall, the trend of adding reasoning capabilities whether via inference-time or train-time compute scaling is a major step forward for LLMs in 2025.

In time, I expect that reasoning will no longer be treated as an optional or special feature but will instead become the standard, much as instruction-finetuned or RLHF-tuned models are now the norm over raw pretrained models.

As mentioned earlier, this article solely focused on inference-time compute length due to its already long lengths, thanks to the very active reasoning research activity. In a future article, I plan to cover all the interesting train-time compute scaling methods for reasoning.

If you read the book and have a few minutes to spare, I'd really appreciate a brief review. It helps us authors a lot!

Your support means a great deal! Thank you!