Understanding Large Language Models -- A Transformative Reading List

Large language models have taken the public attention by storm – no pun intended. In just half a decade large language models – transformers – have almost completely changed the field of natural language processing. Moreover, they have also begun to revolutionize fields such as computer vision and computational biology.

Since transformers have such a big impact on everyone’s research agenda, I wanted to flesh out a short reading list (an extended version of my comment yesterday) for machine learning researchers and practitioners getting started.

The following list below is meant to be read mostly chronologically, and I am entirely focusing on academic research papers. Of course, there are many additional resources out there that are useful. For example,

- the Illustrated Transformer by Jay Alammar;

- a more technical blog article by Lilian Weng;

- a catalog and family tree of all major transformers to date by Xavier Amatriain;

- a minimal code implementation of a generative language model for educational purposes by Andrej Karpathy;

- a lecture series and book chapter by yours truly.

PS: an extended version of this original list, featuring more papers, can be found here at https://magazine.sebastianraschka.com/p/understanding-large-language-models.

Understanding the Main Architecture and Tasks

If you are new to transformers / large language models, it makes the most sense to start at the beginning.

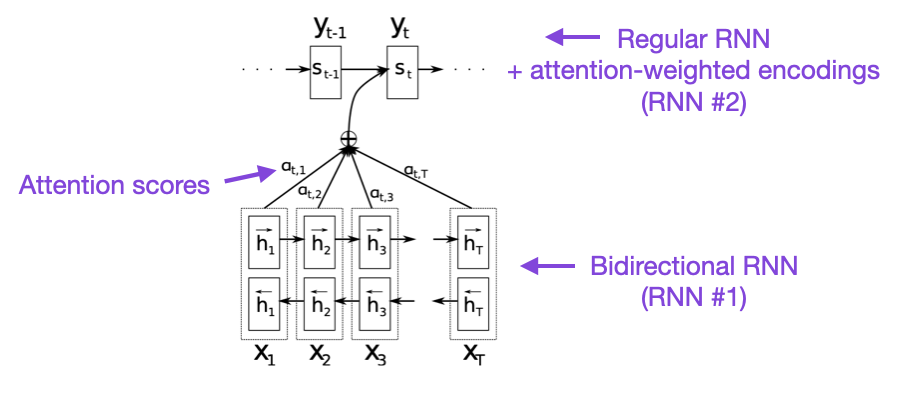

(1) Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate (2014) by Bahdanau, Cho, and Bengio, https://arxiv.org/abs/1409.0473

I recommend beginning with the above paper if you have a few minutes to spare. It introduces an attention mechanism for recurrent neural networks (RNN) to improve long-range sequence modeling capabilities. This allows RNNs to translate longer sentences more accurately – the motivation behind developing the original transformer architecture later.

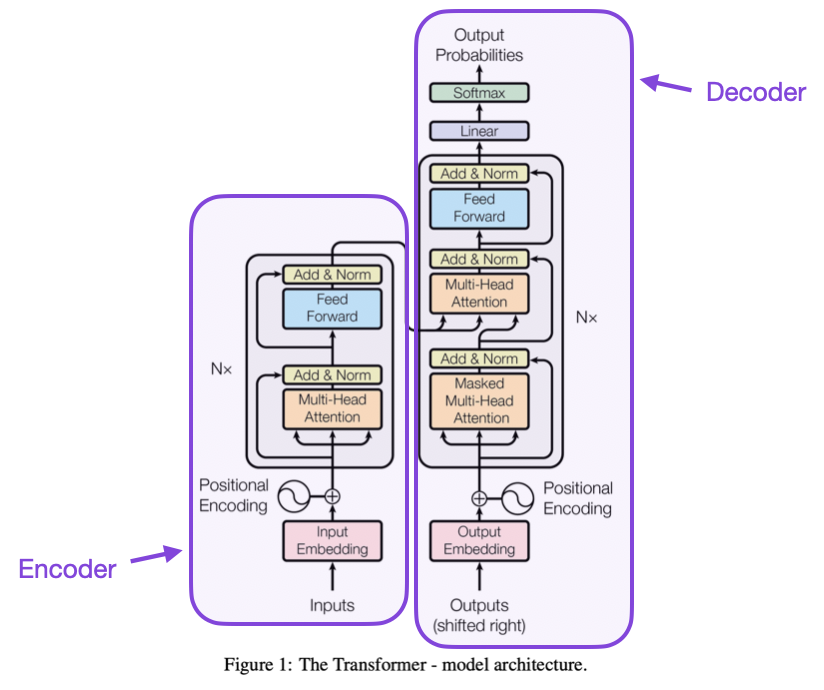

(2) Attention Is All You Need (2017) by Vaswani, Shazeer, Parmar, Uszkoreit, Jones, Gomez, Kaiser, and Polosukhin, https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762

The paper above introduces the original transformer architecture consisting of an encoder- and decoder part that will become relevant as separate modules later. Moreover, this paper introduces concepts such as the scaled dot product attention mechanism, multi-head attention blocks, and positional input encoding that remain the foundation of modern transformers.

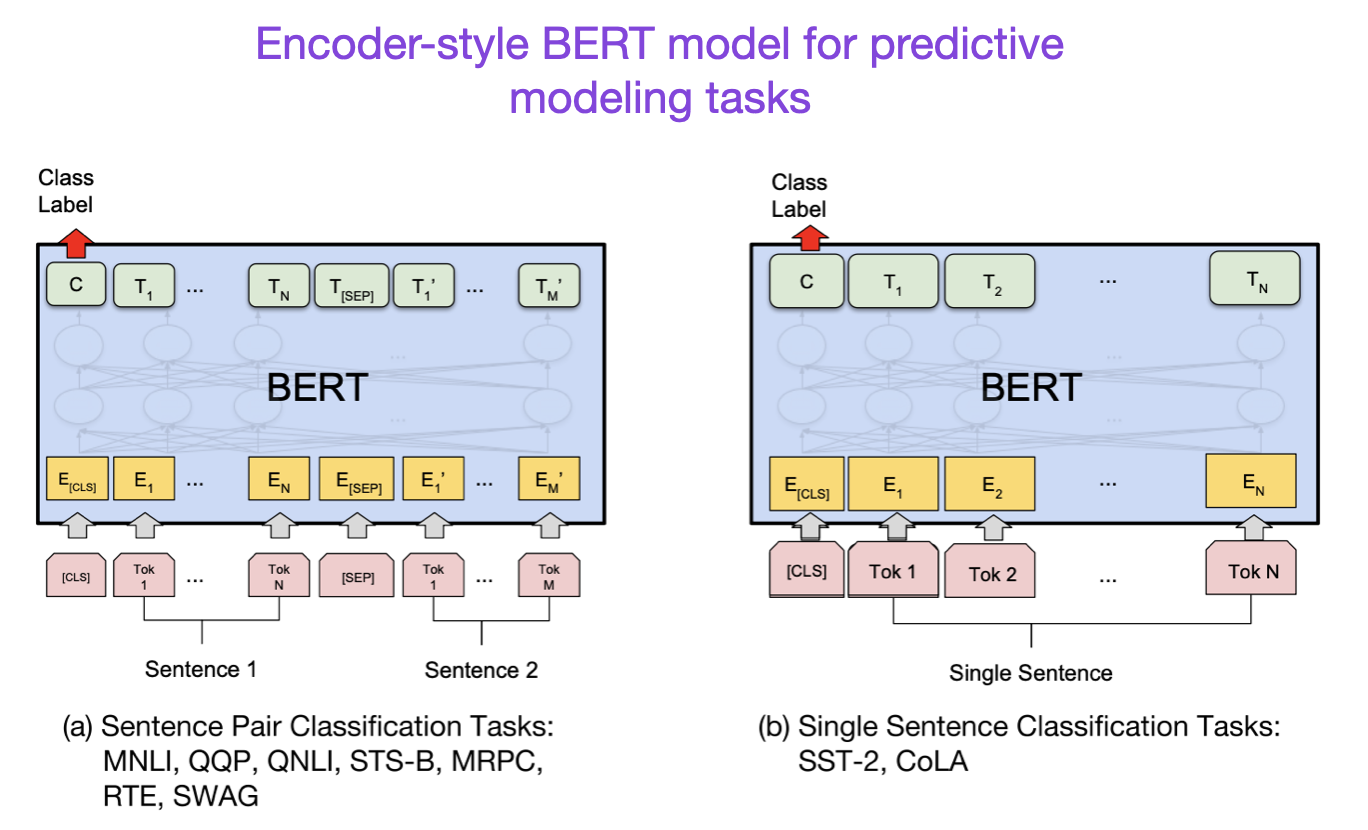

(3) BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding (2018) by Devlin, Chang, Lee, and Toutanova, https://arxiv.org/abs/1810.04805

Following the original transformer architecture, large language model research started to bifurcate in two directions: encoder-style transformers for predictive modeling tasks such as text classification and decoder-style transformers for generative modeling tasks such as translation, summarization, and other forms of text creation.

The BERT paper above introduces the original concept of masked-language modeling, and next-sentence prediction remains an influential decoder-style architecture. If you are interested in this research branch, I recommend following up with RoBERTa, which simplified the pretraining objectives by removing the next-sentence prediction tasks.

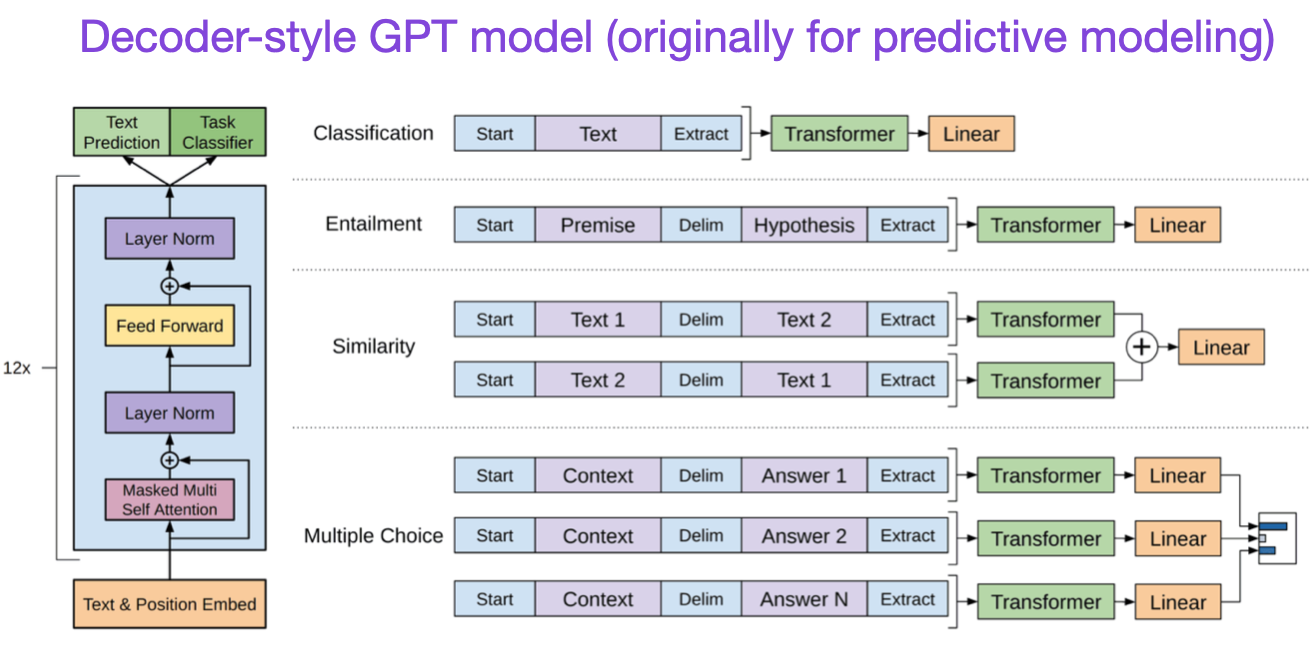

(4) Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training (2018) by Radford and Narasimhan, https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Improving-Language-Understanding-by-Generative-Radford-Narasimhan/cd18800a0fe0b668a1cc19f2ec95b5003d0a5035

The original GPT paper introduced the popular decoder-style architecture and pretraining via next-word prediction. Where BERT can be considered a bidirectional transformer due to its masked language model pretraining objective, GPT is a unidirectional, autoregressive model. While GPT embeddings can also be used for classification, the GPT approach is at the core of today’s most influential LLMs, such as chatGPT.

If you are interested in this research branch, I recommend following up with the GPT-2 and GPT-3 papers. These two papers illustrate that LLMs are capable of zero- and few-shot learning and highlight the emergent abilities of LLMs. GPT-3 is also still a popular baseline and base model for training current-generation LLMs such as ChatGPT – we will cover the InstructGPT approach that lead to ChatGPT later as a separate entry.

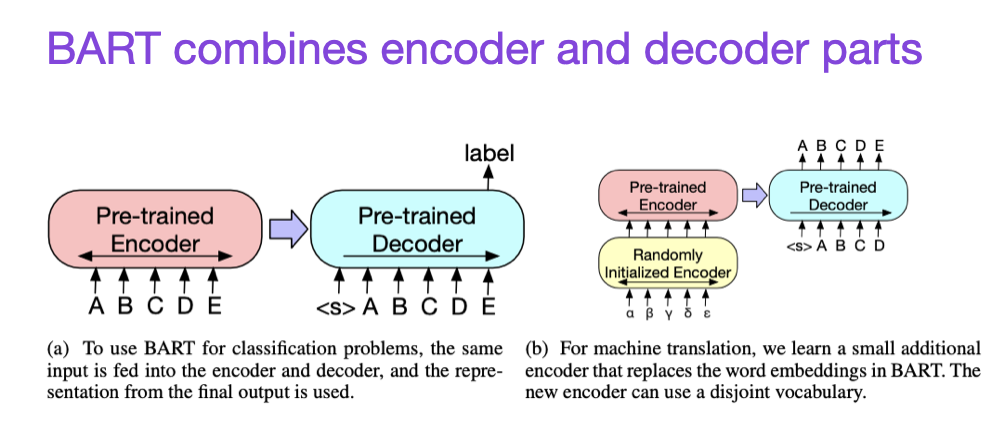

(5) BART: Denoising Sequence-to-Sequence Pre-training for Natural Language Generation, Translation, and Comprehension (2019), by Lewis, Liu, Goyal, Ghazvininejad, Mohamed, Levy, Stoyanov, and Zettlemoyer, https://arxiv.org/abs/1910.13461.

As mentioned earlier, BERT-type encoder-style LLMs are usually preferred for predictive modeling tasks, whereas GPT-type decoder-style LLMs are better at generating texts. To get the best of both worlds, the BART paper above combines both the encoder and decoder parts (not unlike the original transformer – the second paper in this list).

Scaling Laws and Improving Efficiency

If you want to learn more about the various techniques to improve the efficiency of transformers, I recommend the 2020 Efficient Transformers: A Survey paper followed by the 2023 A Survey on Efficient Training of Transformers paper.

In addition, below are papers that I found particularly interesting and worth reading.

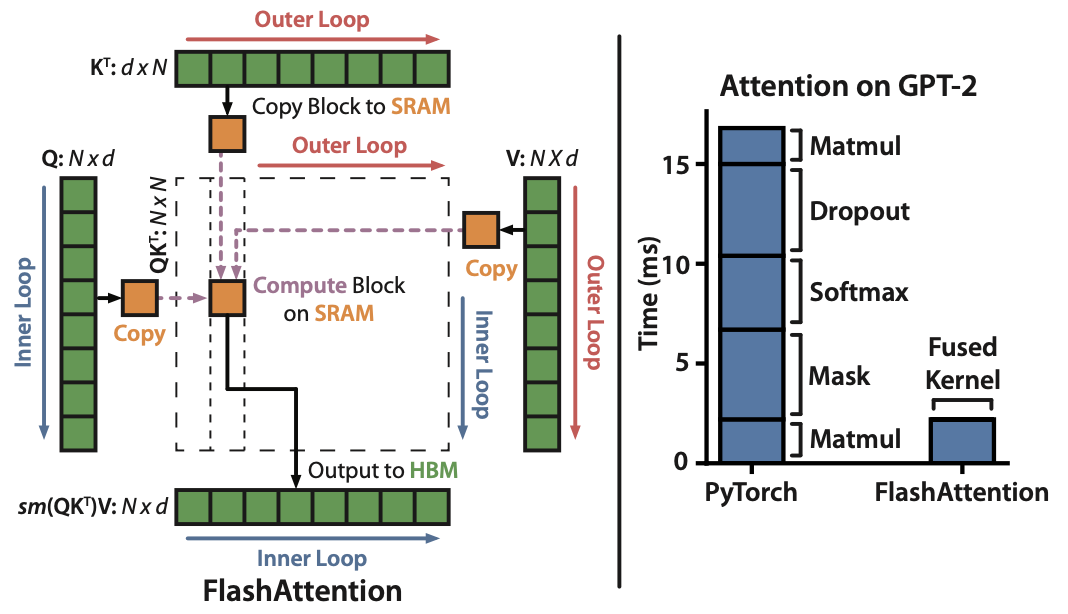

(6) FlashAttention: Fast and Memory-Efficient Exact Attention with IO-Awareness (2022), by Dao, Fu, Ermon, Rudra, and Ré, https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.14135.

While most transformer papers don’t bother about replacing the original scaled dot product mechanism for implementing self-attention, FlashAttention is one mechanism I have seen most often referenced lately.

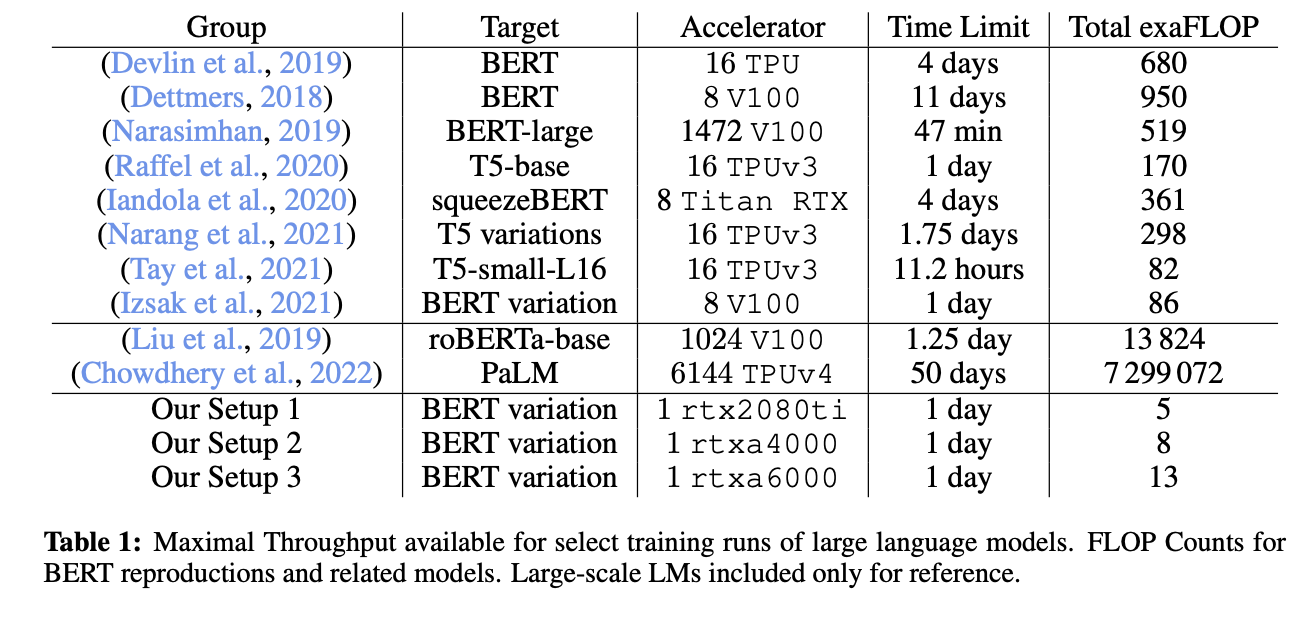

(7) Cramming: Training a Language Model on a Single GPU in One Day (2022) by Geiping and Goldstein, https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.14034.

In this paper, the researchers trained a masked language model / encoder-style LLM (here: BERT) for 24h on a single GPU. For comparison, the original 2018 BERT paper trained it on 16 TPUs for four days. An interesting insight is that while smaller models have higher throughput, smaller models also learn less efficiently. Thus, larger models do not require more training time to reach a specific predictive performance threshold.

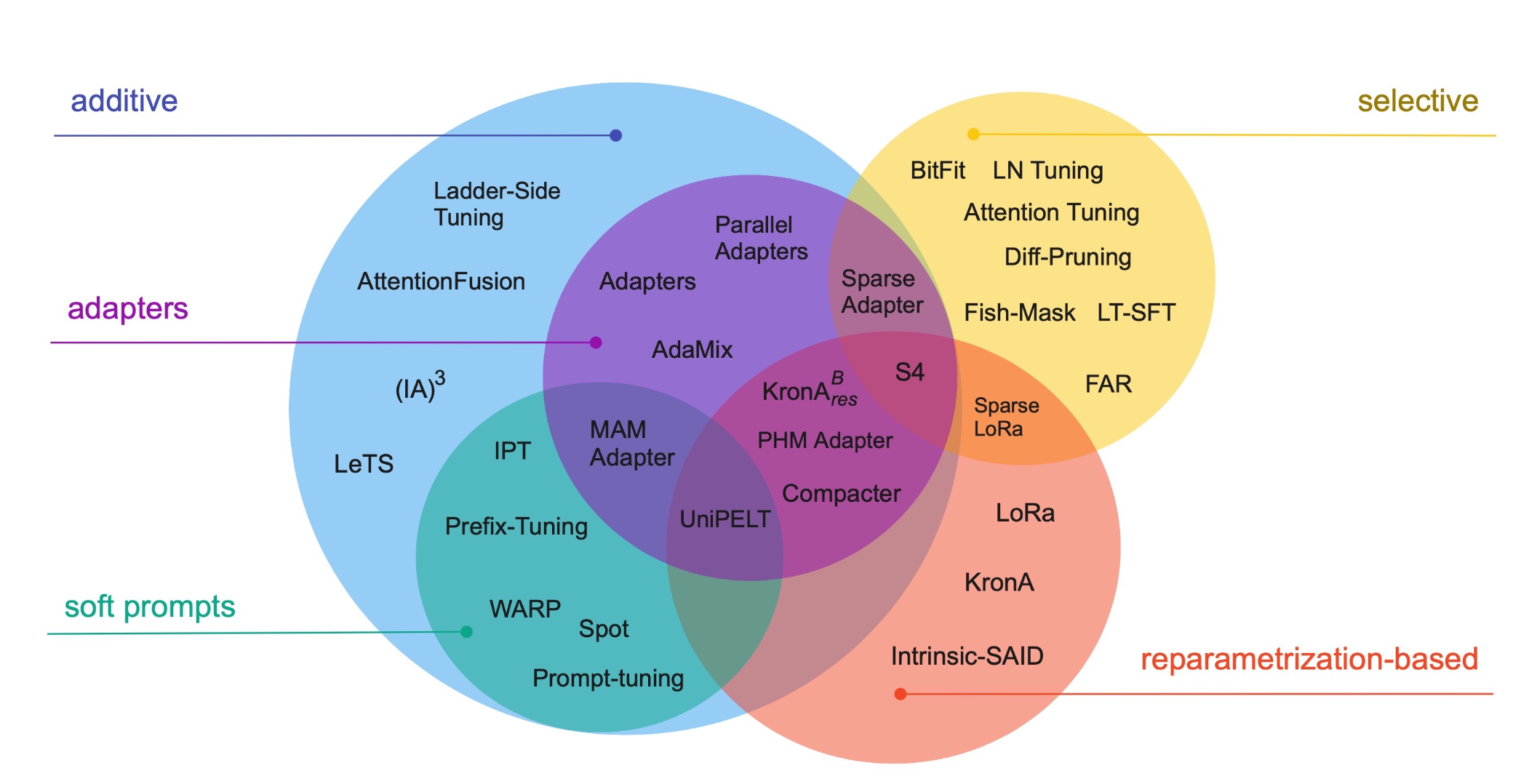

(8) Scaling Down to Scale Up: A Guide to Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (2022) by Lialin, Deshpande, and Rumshisky, https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.15647.

Modern large language models that are pretrained on large datasets show emergent abilities and perform well on various tasks, including language translation, summarization, coding, and Q&A. However, if we want to improve the ability of transformers on domain-specific data and specialized tasks, it’s worthwhile to finetune transformers. This survey reviews more than 40 papers on parameter-efficient finetuning methods (including popular techniques such as prefix tuning, adapters, and low-rank adaptation) to make finetuning (very) computationally efficient.

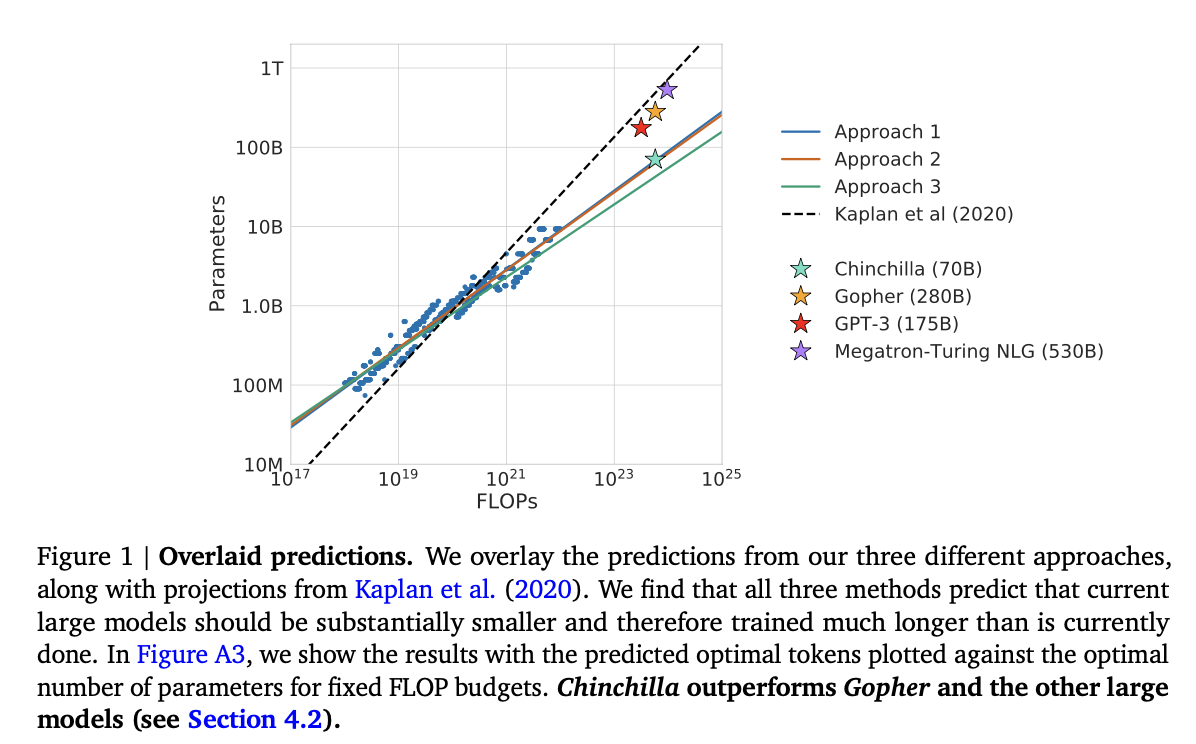

(9) Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models (2022) by Hoffmann, Borgeaud, Mensch, Buchatskaya, Cai, Rutherford, de Las Casas, Hendricks, Welbl, Clark, Hennigan, Noland, Millican, van den Driessche, Damoc, Guy, Osindero, Simonyan, Elsen, Rae, Vinyals, and Sifre, https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.15556.

This paper introduces the 70-billion parameter Chinchilla model that outperforms the popular 175-billion parameter GPT-3 model on generative modeling tasks. However, its main punchline is that contemporary large language models are “significantly undertrained.”

The paper defines the linear scaling law for large language model training. For example, while Chinchilla is only half the size of GPT-3, it outperformed GPT-3 because it was trained on 1.4 trillion (instead of just 300 billion) tokens. In other words, the number of training tokens is as vital as the model size.

Alignment – Steering Large Language Models to Intended Goals and Interests

In recent years, we have seen many relatively capable large language models that can generate realistic texts (for example, GPT-3 and Chinchilla, among others). It seems that we have reached a ceiling in terms of what we can achieve with the commonly used pretraining paradigms.

To make language models more helpful and reduce misinformation and harmful language, researchers designed additional training paradigms to fine-tune the pretrained base models.

(10) Training Language Models to Follow Instructions with Human Feedback (2022) by Ouyang, Wu, Jiang, Almeida, Wainwright, Mishkin, Zhang, Agarwal, Slama, Ray, Schulman, Hilton, Kelton, Miller, Simens, Askell, Welinder, Christiano, Leike, and Lowe, https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.02155.

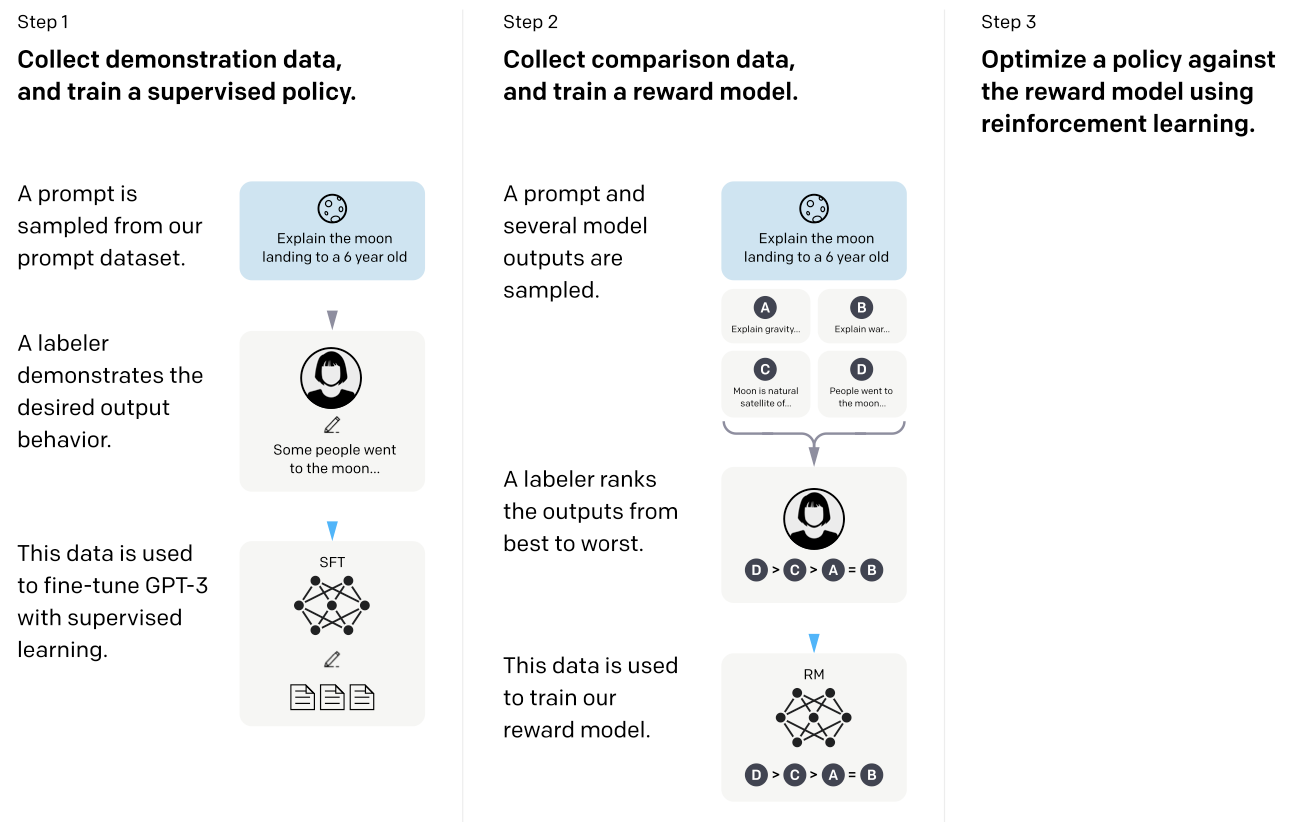

In this so-called InstructGPT paper, the researchers use a reinforcement learning mechanism with humans in the loop (RLHF). They start with a pretrained GPT-3 base model and fine-tune it further using supervised learning on prompt-response pairs generated by humans (Step 1). Next, they ask humans to rank model outputs to train a reward model (step 2). Finally, they use the reward model to update the pretrained and fine-tuned GPT-3 model using reinforcement learning via proximal policy optimization (step 3).

As a sidenote, this paper is also known as the paper describing the idea behind ChatGPT – according to the recent rumors, ChatGPT is a scaled-up version of InstructGPT that has been fine-tuned on a larger dataset.

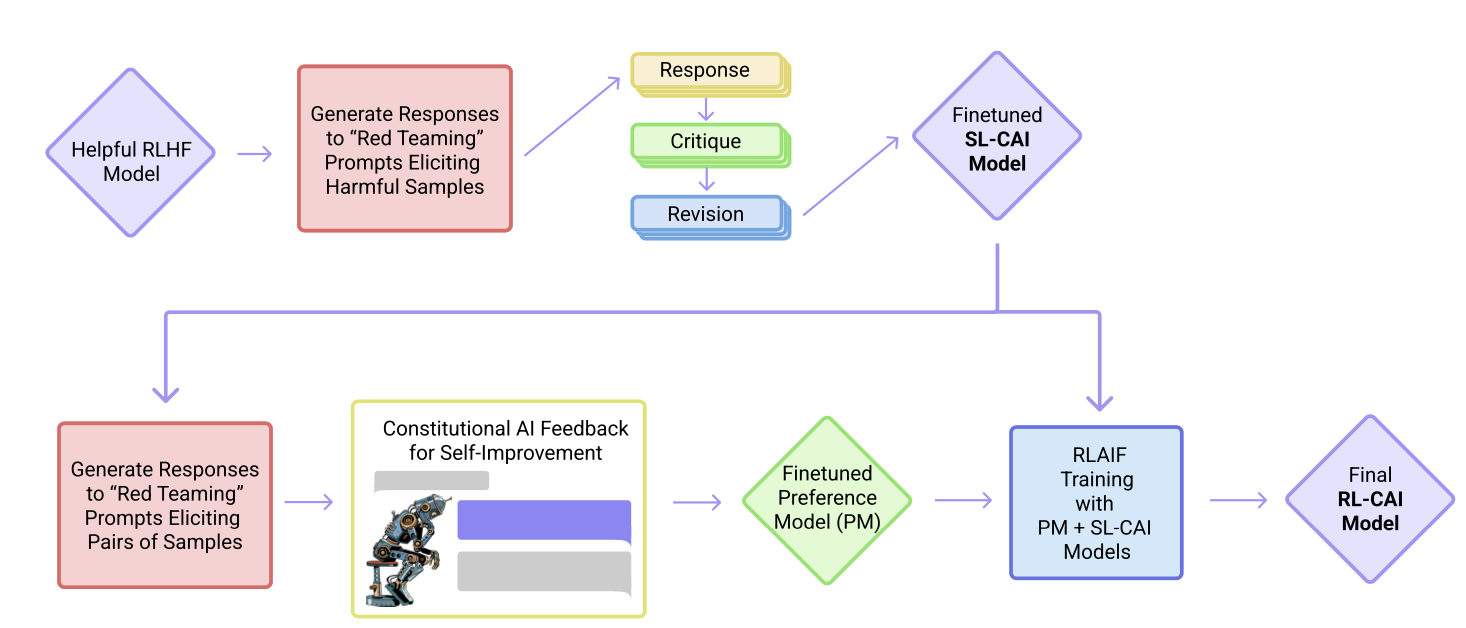

(11) Constitutional AI: Harmlessness from AI Feedback (2022) by Yuntao, Saurav, Sandipan, Amanda, Jackson, Jones, Chen, Anna, Mirhoseini, McKinnon, Chen, Olsson, Olah, Hernandez, Drain, Ganguli, Li, Tran-Johnson, Perez, Kerr, Mueller, Ladish, Landau, Ndousse, Lukosuite, Lovitt, Sellitto, Elhage, Schiefer, Mercado, DasSarma, Lasenby, Larson, Ringer, Johnston, Kravec, El Showk, Fort, Lanham, Telleen-Lawton, Conerly, Henighan, Hume, Bowman, Hatfield-Dodds, Mann, Amodei, Joseph, McCandlish, Brown, Kaplan, https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.08073.

In this paper, the researchers are taking the alignment idea one step further, proposing a training mechanism for creating a “harmless” AI system. Instead of direct human supervision, the researchers propose a self-training mechanism that is based on a list of rules (which are provided by a human). Similar to the InstructGPT paper mentioned above, the proposed method uses a reinforcement learning approach.

Bonus: Introduction to Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF)

While RLHF (reinforcement learning with human feedback) may not completely solve the current issues with LLMs, it is currently considered the best option available, especially when compared to previous-generation LLMs. It is likely that we will see more creative ways to apply RLHF to LLMs other domains.

The two papers above, InstructGPT and Consitutinal AI, make use of RLHF, and since it is going to be an influential method in the near future, this section includes additional resources if you want to learn about RLHF. (To be technicallty correct, the Constitutional AI paper uses AI instead of human feedback, but it follows a similar concept using RL.)

(12) Asynchronous Methods for Deep Reinforcement Learning (2016) by Mnih, Badia, Mirza, Graves, Lillicrap, Harley, Silver, and Kavukcuoglu (https://arxiv.org/abs/1602.01783) introduces policy gradient methods as an alternative to Q-learning in deep learning-based RL.

(13) Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms (2017) by Schulman, Wolski, Dhariwal, Radford, Klimov (https://arxiv.org/abs/1707.06347) presents a modified proximal policy-based reinforcement learning procedure that is more data-efficient and scalable than the vanilla policy optimization algorithm above.

(14) Fine-Tuning Language Models from Human Preferences (2020) by Ziegler, Stiennon, Wu, Brown, Radford, Amodei, Christiano, Irving (https://arxiv.org/abs/1909.08593) illustrates the concept of PPO and reward learning to pretrained language models including KL regularization to prevent the policy from diverging too far from natural language.

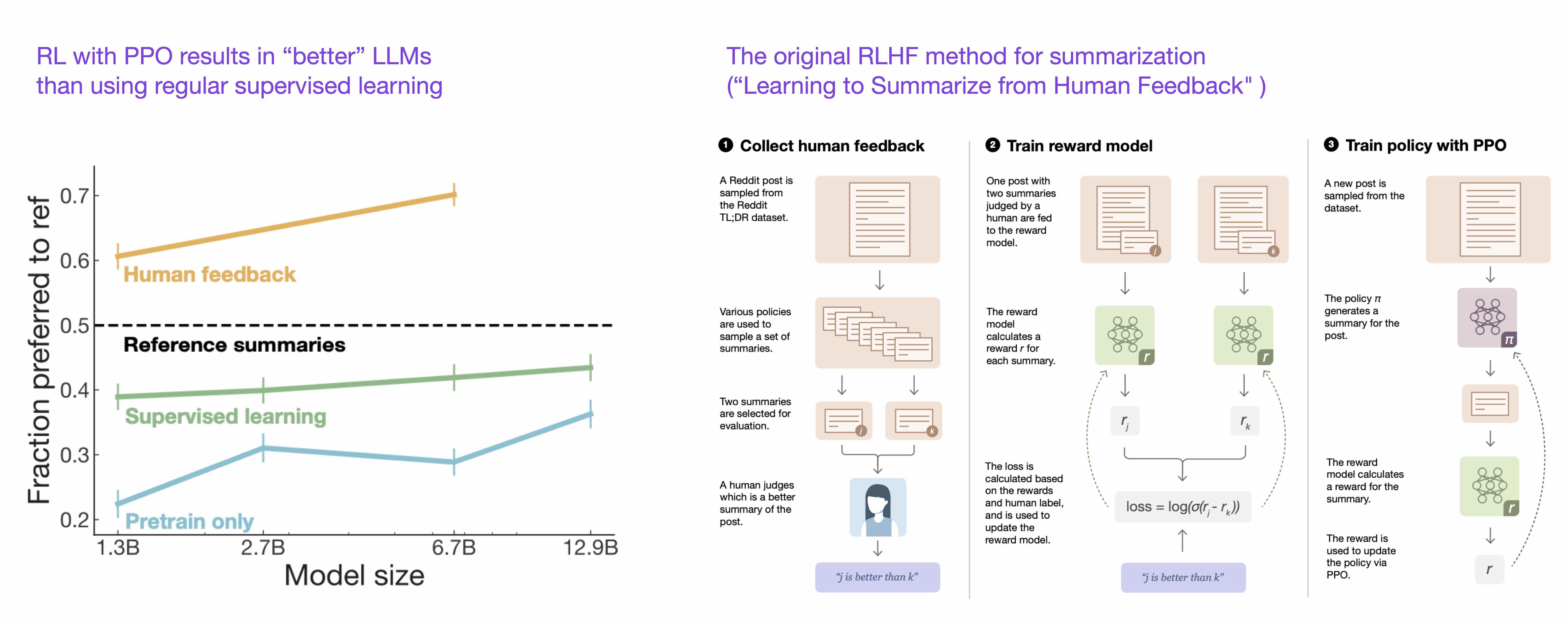

(15) Learning to Summarize from Human Feedback (2022) by Stiennon, Ouyang, Wu, Ziegler, Lowe, Voss, Radford, Amodei, Christiano https://arxiv.org/abs/2009.01325 introduces the popular RLHF three-step procedure:

- pretraining GPT-3

- fine-tuning it in a supervised fashion, and

- training a reward model also in a supervised fashion. The fine-tuned model is then trained using this reward model with proximal policy optimization.

This paper also shows that reinforcement learning with proximal policy optimization results in better models than just using regular supervised learning.

(16) Training Language Models to Follow Instructions with Human Feedback (2022) by Ouyang, Wu, Jiang, Almeida, Wainwright, Mishkin, Zhang, Agarwal, Slama, Ray, Schulman, Hilton, Kelton, Miller, Simens, Askell, Welinder, Christiano, Leike, and Lowe (https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.02155), also known as InstructGPT paper)uses a similar three-step procedure for RLHF as above, but instead of summarizing text, it focuses on generating text based on human instructions. Also, it uses a labeler to rank the outputs from best to worst (instead of just a binary comparison between human- and AI-generated texts).

Conclusion and Further Reading

I tried to keep the list above nice and concise, focusing on the top-10 papers (plus 3 bonus papers on RLHF) to understand the design, constraints, and evolution behind contemporary large language models.

For further reading, I suggest following the references in the papers mentioned above. Or, to give you some additional pointers, here are some additional resources:

Open-source alternatives to GPT

-

BLOOM: A 176B-Parameter Open-Access Multilingual Language Model (2022), https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.05100

-

OPT: Open Pre-trained Transformer Language Models (2022), https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.01068

ChatGPT alternatives

-

LaMDA: Language Models for Dialog Applications (2022), https://arxiv.org/abs/2201.08239

-

(Sparrow) Improving Alignment of Dialogue Agents via Targeted Human Judgements (2022), https://arxiv.org/abs/2209.14375

-

BlenderBot 3: A Deployed Conversational Agent that Continually Learns to Responsibly Rngage, https://arxiv.org/abs/2208.03188

Large language models in computational biology

-

ProtTrans: Towards Cracking the Language of Life’s Code Through Self-Supervised Deep Learning and High Performance Computing (2021), https://arxiv.org/abs/2007.06225

-

Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold (2021), https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03819-2

-

Large Language Models Generate Functional Protein Sequences Across Diverse Families (2023), https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587-022-01618-2

This blog is personal passion project that does not offer direct compensation. However, for those who wish to support me, please consider purchasing a copy of one of my books. If you find them insightful and beneficial, please feel free to recommend them to your friends and colleagues.

Your support means a great deal! Thank you!